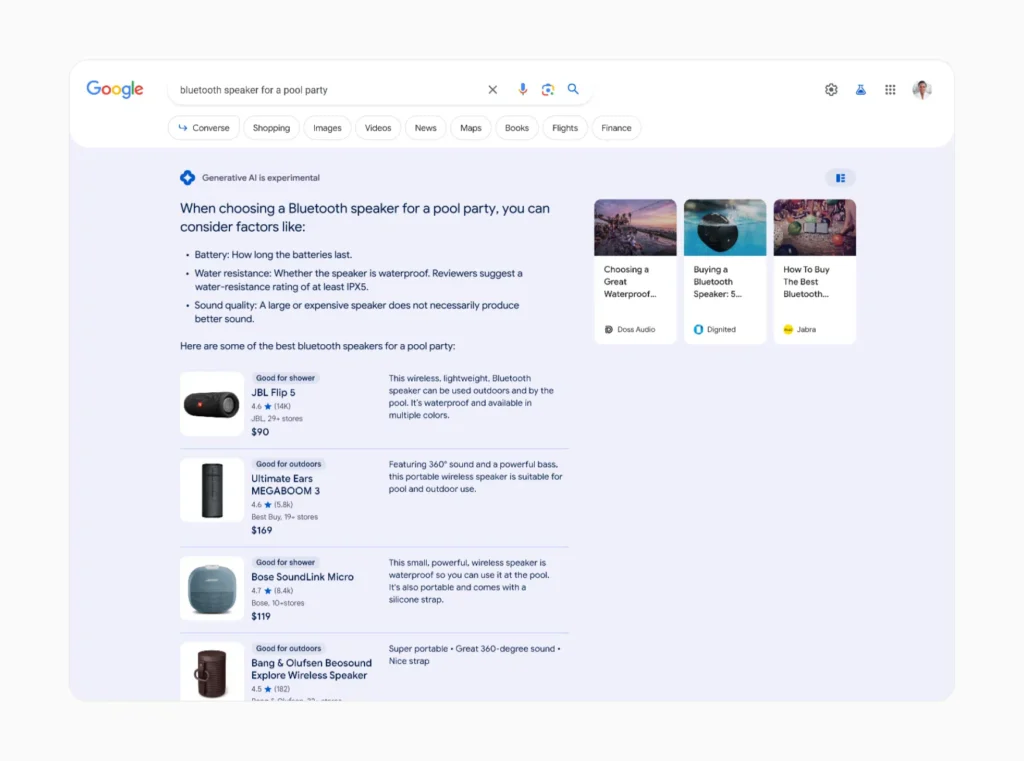

Google’s latest flagship I/O conference saw the company double down on its Search Generative Experience (SGE) – which will embed generative AI into Google Search.

SGE, which aims to bring AI-generated answers to over a billion users by the end of 2024, relies on Gemini, Google’s family of large language models (LLMs), to generate human-like responses to search queries.

Instead of a traditional Google search, which primarily displays links, you’ll be presented with an AI-generated summary alongside other results.

This “AI Overview” has been criticized for providing nonsense information, and Google is fast working on solutions before it begins mass rollout.

But aside from recommending adding glue on pizza and saying pythons are mammals, there’s another bugbear with Google’s new AI-driven search strategy: its environmental footprint.

Why SGE is resource-intensive

While traditional search engines simply retrieve existing information from the internet, generative AI systems like SGE must create entirely new content for each query.

This process requires vastly more computational power and energy than conventional search methods.

It’s estimated that between 3 and 10 billion Google searches are conducted daily. The impacts of applying AI to even a small percentage of those searches could be incredible.

Sasha Luccioni, a researcher at the AI company Hugging Face who studies the environmental impact of these technologies, recently discussed the sharp increase in energy consumption SGE might trigger.

Luccioni and her team estimate that generating search information with AI could require 30 times as much energy as a conventional search.

“It just makes sense, right? While a mundane search query finds existing data from the Internet, applications like AI Overviews must create entirely new information,” she told Scientific American.

In 2023, Luccioni and her colleagues found that training the LLM BLOOM emitted greenhouse gases equivalent to 19 kilograms of CO2 per day of use, or the amount generated by driving 49 miles in an average gas-powered car. They also found that generating just two images using AI can consume as much energy as fully charging an average smartphone.

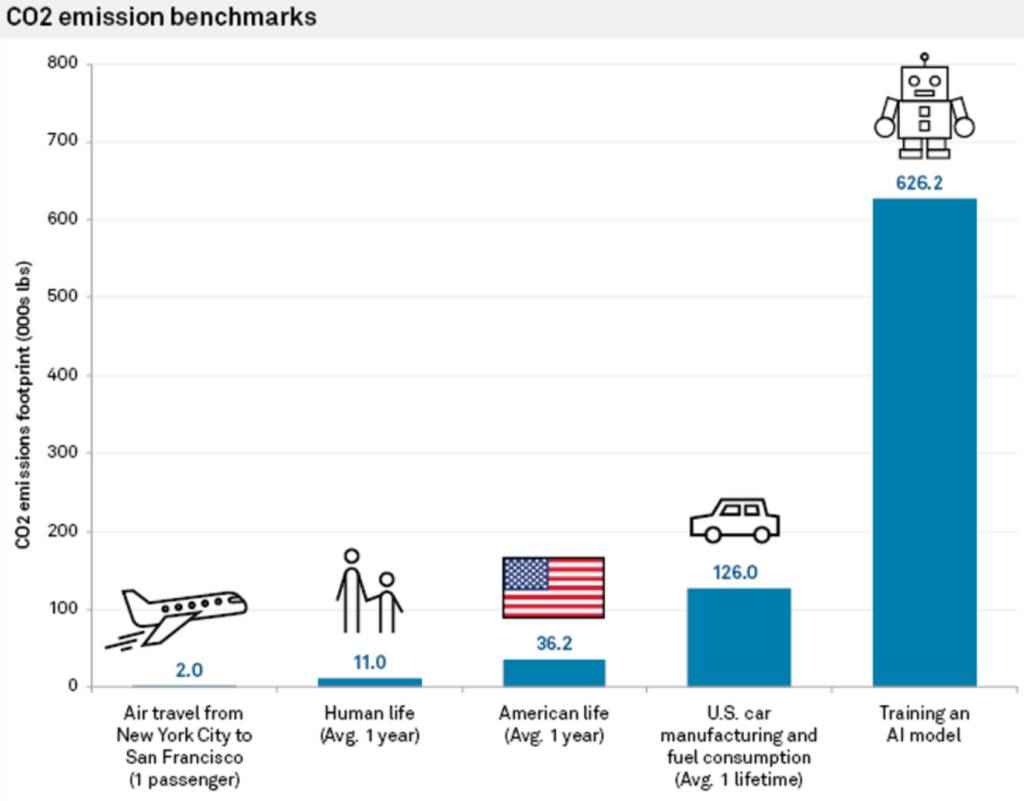

Previous studies estimated that the CO2 emissions associated with training an AI model might exceed those of hundreds of commercial flights or the average car over its lifetime.

In an interview with Reuters last year, John Hennessy, chair of Google’s parent company, Alphabet, himself admitted to the increased costs associated with AI-powered search.

“An exchange with a large language model could cost ten times more than a traditional search,” he stated, although he predicted costs to decrease as the models are fine-tuned.

AI search’s strain on infrastructure and resources

Data centers housing AI servers are projected to double their energy consumption by 2026, potentially using as much power as a small country.

With chip manufacturers like NVIDIA rolling out bigger, more powerful chips, it could soon take the equivalent of multiple nuclear power stations to run large-scale AI workloads.

When AI companies respond to questions about how this can be sustained, they typically quote renewables’ increased efficiency and capacity and improved power efficiency of AI hardware.

However, the transition to renewable energy sources for data centers is proving to be slow and complex.

As Shaolei Ren, a computer engineer at the University of California, Riverside, who studies sustainable AI, explained, “There’s a supply and demand mismatch for renewable energy. The intermittent nature of renewable energy production often fails to match the constant, stable power required by data centers.”

Because of this mismatch, fossil fuel plants are being kept online longer than planned in areas with high concentrations of tech infrastructure.

Another solution to energy woes lies in energy-efficient AI hardware. NVIDIA’s new Blackwell chip is many times more energy-efficient than its predecessors, and other companies like Delta are working on efficient data center hardware.

Rama Ramakrishnan, an MIT Sloan School of Management professor, explained that while the number of searches going through LLMs is likely to increase, the cost per query seems to decrease as companies work to make hardware and software more efficient.

But will that be enough to offset increasing energy demands? “It’s difficult to predict,” Ramakrishnan says. “My guess is that it’s probably going to go up, but it’s probably not going to go up dramatically.”

As the AI race heats up, mitigating environmental impacts has become necessary. Necessity is the mother of invention, and tech companies are under pressure to create solutions to keep AI’s momentum rolling.

Energy-efficient hardware, renewables, and even fusion power can pave the way to a more sustainable future for AI, but the journey is littered with uncertainty.

SGE could strain water supplies, too

We can also speculate about the water demands created by SGE, which could mirror the vast increases in data center water consumption attributed to generative AI industry.

According to recent Microsoft environmental reports, water consumption has rocketed by up to 50% in some regions, with the Las Vegas data center water consumption doubling since 2022. Google’s reports also registered a 20% increase in data center water expenditure in 2023 compared to 2022.

Ren attributes the majority of this growth to AI, stating, “It’s fair to say the majority of the growth is due to AI, including Microsoft’s heavy investment in generative AI and partnership with OpenAI.”

Ren estimated that each interaction with ChatGPT, consisting of 5 to 50 prompts, consumes a staggering 500ml of water.

In a paper published in 2023, Ren’s team wrote, “The global AI demand may be accountable for 4.2 – 6.6 billion cubic meters of water withdrawal in 2027, which is more than the total annual water withdrawal of 4 – 6 Denmark or half of the United Kingdom.”

Using Ren’s research, we can create some napkin calculations for how Google’s SGE might factor into these predictions.

Let’s say Google processes an average of 8.5 billion daily searches worldwide. Assuming that even a fraction of these searches, say 10%, utilize SGE and generate AI-powered responses with an average of 50 words per response, the water consumption could be phenomenal.

Using Ren’s estimate of 500 milliliters of water per 5 to 50 prompts (say, a single session on Google SGE), we can roughly calculate that 850 million SGE-powered searches (10% of Google’s daily searches) would consume approximately 425 million liters of water daily.

This is equivalent to the daily water consumption of a city with a population of over 2.5 million people.

In reality, actual water consumption may vary depending on factors such as the efficiency of Google’s data centers and the specific implementation and scale of SGE.

Nevertheless, it’s very reasonable to speculate that SGE and other forms of AI search will further ramp up AI’s resource usage.

Will global AI experiences like SGE be sustainable at a massive scale? Numerous factors are at play, but it’ll be no walk in the park.