Digital colonialism refers to the dominance of tech giants and powerful entities over the digital landscape, shaping the flow of information, knowledge, and culture to serve their interests.

This dominance is not just about controlling digital infrastructure but also about influencing the narratives and knowledge structures that define our digital age.

Digital colonialism, and now AI colonialism, are widely acknowledged terms, and institutions such as MIT have researched and written about them extensively.

Top researchers from Anthropic, Google, DeepMind, and other tech companies have openly discussed AI’s limited scope in serving people from diverse backgrounds, particularly in reference to bias in machine learning systems.

Machine learning systems fundamentally reflect the data they’re trained on – data that could be viewed as a product of our digital zeitgeist – a collection of prevailing narratives, images, and ideas that dominate the online world.

But who gets to shape these informational forces? Whose voices are amplified, and whose are attenuated?

When AI learns from training data, it inherits specific worldviews that might not necessarily resonate with or represent global cultures and experiences. In addition, the controls that govern the output of generative AI tools are shaped by underlying socio-cultural vectors.

This has led developers like Anthropic to seek democratic methods of shaping AI behavior using public views.

As Jack Clark, Anthropic’s policy chief, described a recent experiment from his company, “We’re trying to find a way to develop a constitution that is developed by a whole bunch of third parties, rather than by people who happen to work at a lab in San Francisco.”

Current generative AI training paradigms risk creating a digital echo chamber where the same ideas, values, and perspectives are continuously reinforced, further entrenching the dominance of those already overrepresented in the data.

As AI embeds itself into complex decision-making, from social welfare and recruitment to financial decisions and medical diagnoses, lopsided representation leads to real-world biases and injustices.

Datasets are geographically and culturally situated

A recent study by the Data Provenance Initiative probed 1,800 popular datasets intended for natural language processing (NLP), a discipline of AI that focuses on language and text.

NLP is the dominant machine learning methodology behind large language models (LLMs), including ChatGPT and Meta’s Llama models.

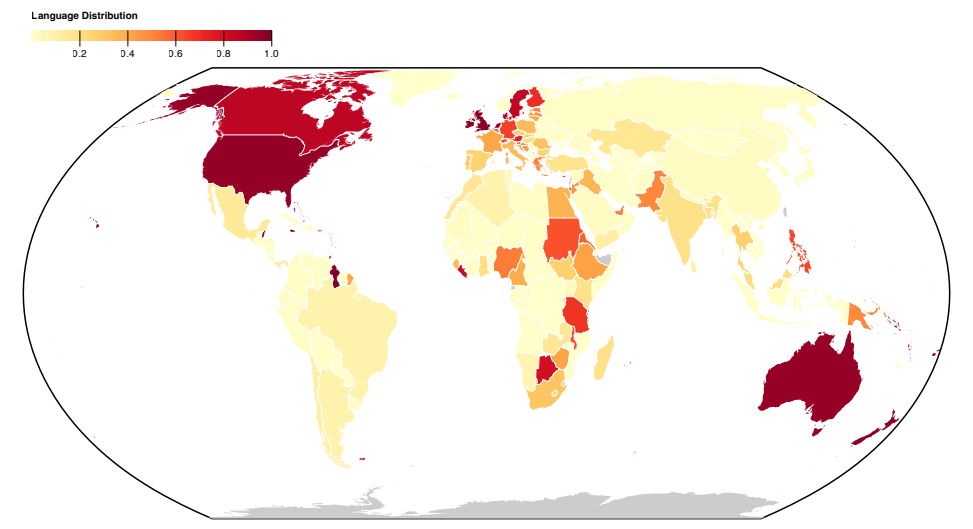

The study reveals a Western-centric skew in language representation across datasets, with English and Western European languages defining text data.

Languages from Asian, African, and South American nations are markedly underrepresented.

Resultantly, LLMs can’t hope to accurately represent the cultural-linguistic nuances of these regions to the same extent as Western languages.

Even when languages from the Global South appear to be represented, the source and dialect of the language primarily originate from North American or European creators and web sources.

A previous Anthropic experiment found that switching languages in models like ChatGPT still yielded Western-centric views and stereotypes in conversations.

Anthropic researchers concluded, “If a language model disproportionately represents certain opinions, it risks imposing potentially undesirable effects such as promoting hegemonic worldviews and homogenizing people’s perspectives and beliefs.”

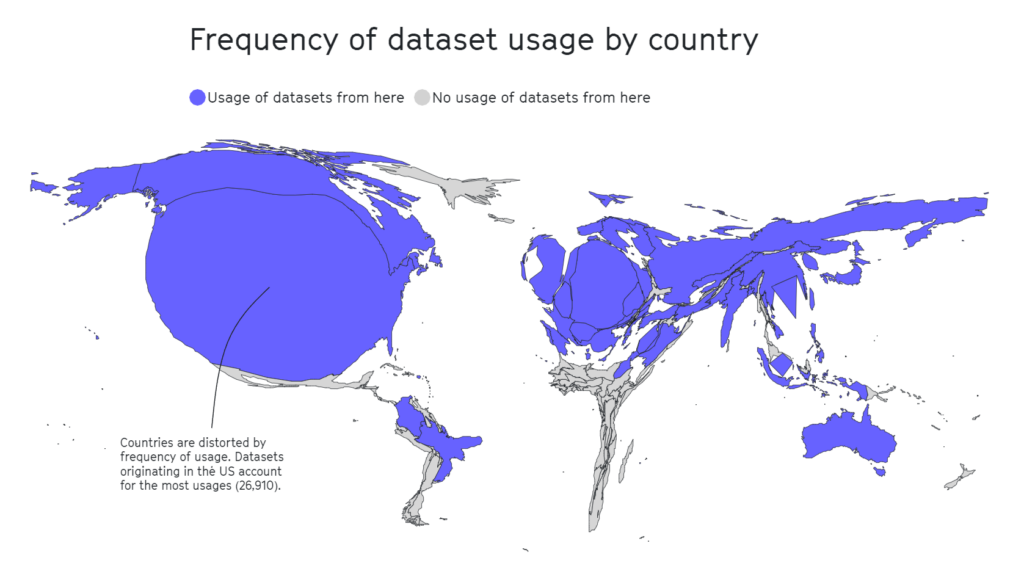

The Data Provenance study also dissected the geographic landscape of dataset curation. Academic organizations emerge as the primary drivers, contributing to 69% of the datasets, followed by industry labs (21%) and research institutions (17%).

Notably, the largest contributors are AI2 (12.3%), the University of Washington (8.9%), and Facebook AI Research (8.4%).

A separate 2020 study highlights that half of the datasets used for AI evaluation across approximately 26,000 research articles originated from as few as 12 top universities and tech companies.

Again, geographic areas such as Africa, South and Central America, and Central Asia were found to be woefully underrepresented, as viewed below.

In other research, influential datasets like MIT’s Tiny Images or Labeled Faces in the Wild carried primarily white Western male images, with some 77.5% males and 83.5% white-skinned individuals in the case of Labeled Faces in the Wild.

In the case of Tiny Images, a 2020 analysis by The Register found that many Tiny Images contained obscene, racist, and sexist labels.

Antonio Torralba from MIT said they weren’t aware of the labels, and the dataset was deleted. Torralba said, “It is clear that we should have manually screened them.”

English dominates the AI ecosystem

Pascale Fung, a computer scientist and director of the Center for AI Research at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, discussed the problems associated with hegemonic AI.

Fung refers to over 15 research papers investigating the multilingual proficiency of LLMs and consistently finding them lacking, particularly when translating English into other languages. For example, languages with non-Latin scripts, like Korean, expose LLMs’ limitations.

In addition to poor multilingual support, other studies suggest the majority of bias benchmarks and measures have been developed with English language models in mind.

Non-English bias benchmarks are few and far between, leading to a significant gap in our ability to assess and rectify bias in multilingual language models.

There are signs of improvement, such as Google’s efforts with its PaLM 2 language model and Meta’s Massively Multilingual Speech (MMS) that can identify more than 4,000 spoken languages, 40 times more than other approaches. However, MMS remains experimental.

Researchers are creating diverse, multilingual datasets, but the overwhelming amount of English text data, often free and easy to access, makes it the de facto choice for developers.

Beyond data: structural issues in AI labor

MIT’s vast review of AI colonialism drew attention to a relatively hidden aspect of AI development – exploitative labor practices.

AI has triggered an intense rise in the demand for data-labeling services. Companies like Appen and Sama have emerged as key players, offering the services of tagging text, images, and videos, sorting photos, and transcribing audio to feed machine learning models.

Human data specialists also manually label content types, often to sort data that contains illegal, illicit, or unethical content, such as descriptions of sexual abuse, harmful behavior, or other illegal activities.

While AI companies automate some of these processes, it’s still vital to keep ‘humans in the loop’ to ensure model accuracy and safety compliance.

The market value of this “ghost work,” as termed by anthropologist Mary Gray and social scientist Siddharth Suri, is projected to skyrocket to $13.7 billion by 2030.

Ghost work often involves exploiting cheap labor, particularly from economically vulnerable countries. Venezuela, for instance, has become a primary source of AI-related labor due to its economic crisis.

As the country grappled with its worst peacetime economic catastrophe and astronomic inflation, a significant portion of its well-educated and internet-connected population turned to crowd-working platforms as a means of survival.

The confluence of a well-educated workforce and economic desperation made Venezuela an attractive market for data-labeling companies.

This is not a controversial point – when MIT publishes articles with titles like “Artificial intelligence is creating a new colonial world order,” referencing scenarios such as this, it’s clear that some in the industry seek to retract the curtain on these underhand labor practices.

As MIT reports, for many Venezuelans, the burgeoning AI industry has been a double-edged sword. While it provided an economic lifeline amid desperation, it also exposed people to exploitation.

Julian Posada, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, highlights the “huge power imbalances” in these working arrangements. The platforms dictate the rules, leaving workers with little say and limited financial compensation despite on-the-job challenges such as exposure to disturbing content.

This dynamic is eerily reminiscent of historical colonial practices where empires exploited the labor of vulnerable countries, extracting profits and deserting them once the opportunity dwindled, often because ‘better value’ was available elsewhere.

Similar situations have been observed in Nairobi, Kenya, where a group of former content moderators working on ChatGPT lodged a petition with the Kenyan government.

They alleged “exploitative conditions” during their tenure with Sama, a US-based data annotation services company contracted by OpenAI. The petitioners claimed that they were exposed to disturbing content without adequate psychosocial support, leading to severe mental health issues, including PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

Documents reviewed by TIME indicated that OpenAI had signed contracts with Sama worth around $200,000. These contracts involved labeling descriptions of sexual abuse, hate speech, and violence.

The impact on the mental health of the workers was profound. Mophat Okinyi, a former moderator, spoke of the psychological toll, describing how exposure to graphic content led to paranoia, isolation, and significant personal loss.

The wages for such distressing work were shockingly low – a Sama spokesperson disclosed that workers earned between $1.46 and $3.74 an hour.

Resisting digital colonialism

If the AI industry has become a new frontier of digital colonialism, then resistance is already becoming more cohesive.

Activists, often bolstered by support from AI researchers, are advocating for accountability, policy changes, and the development of technologies that prioritize the needs and rights of local communities.

Nanjala Nyabola’s Kiswahili Digital Rights Project offers an innovative example of how local-scale grassroots projects can install the infrastructure required to protect communities from digital hegemony.

The project considers the hegemony of Western regulations when defining a group’s digital rights, as not everyone is protected by the intellectual property, copyright, and privacy laws many of us take for granted. This leaves significant proportions of the global population liable to exploitation by technology companies.

Recognizing that discussions surrounding digital rights are blunted if people can’t communicate issues in their native languages, Nyabola and her team translated key digital rights and technology terms into the Kiswahili language, primarily spoken in Tanzania, Kenya, and Mozambique.

Nyabola described of the project, “During that process [of the Huduma Namba initiative], we didn’t really have the language and the tools to explain to non-specialist or non-English language speaking communities in Kenya what the implications of the initiative were.”

In a similar grassroots project, Te Hiku Media, a non-profit radio station broadcasting primarily in the Māori language, held a vast database of recordings spanning decades, many of which echoed the voices of ancestral phrases no longer spoken.

Mainstream speech recognition models, similar to LLMs, tend to underdeliver when prompted in different languages or English dialects.

The Te Hiku Media collaborated with researchers and open-source technologies to train a speech recognition model tailored for the Māori language. Māori activist Te Mihinga Komene contributed some 4,000 phrases to countless others who participated in the project.

The resulting model and data are protected under the Kaitiakitanga License – Kaitiakitanga is a Māori word without a specific English definition but is similar to “guardian” or “custodian.”

Keoni Mahelona, a co-founder of Te Hiku Media, poignantly remarked, “Data is the last frontier of colonisation.”

These projects have inspired other indigenous and native communities under pressure from digital colonialism and other forms of social upheaval, such as the Mohawk peoples in North America and Native Hawaiians.

As open-source AI becomes cheaper and easier to access, iterating and fine-tuning models using unique localized datasets should become simpler, enhancing cross-cultural access to the technology.

While the AI industry remains young, the time is now to bring these challenges to the fore so people can collectively evolve solutions.

Solutions can be both macro-level, in the form of regulations, policies, and machine learning training approaches, and micro-level, in the form of local and grassroots projects.

Together, researchers, activists, and local communities can find methods to ensure AI benefits everyone.