Artists and creators are putting AI developers to the sword over potential copyright infringement.

Type a prompt into an AI image generator such as DALL-E, MidJourney, or Stable Diffusion, and it’ll produce a seemingly unique image within mere seconds.

Despite their apparent uniqueness, these images are generated from billions of other images via what can be described as a complex digital collaging technique.

The source images are scraped from ‘public’ or ‘open’ sources.

If you ask ChatGPT how an image generator like DALL-E works, it’ll say something like, “Think of DALL-E like a super advanced digital artist, who has seen millions of images and can draw a new one based on your description, trying to make it as accurate as possible. It’s doing this by mixing and matching elements it has learned from its previous ‘observations.'”

It’s a bit like roaming the world’s art galleries and taking photos of each piece of work – except you can’t be kicked out.

The internet doesn’t have security guards and cameras watching people to prevent piracy or theft, and the practice of data scraping – which involves collecting data from the internet with the service of bots – has always occupied nebulous legal territory.

Artists argue that training text-to-image AIs on public datasets is equivalent to the world’s greatest art heist.

How do AI detectors make artists feel?

For some successful artists whose work has been copied thousands – even millions of times – the impacts of AI-generated art have made it difficult to distinguish between their own work and AI copies.

The aesthetic differences are simply too small, probably because popular images appear prolifically in datasets.

Among those is Greg Rutowski, who said, “My work has been used in AI more than Picasso.”

Rutowki’s fantasy illustrations feature in franchises such as Dungeons and Dragons and Magic: The Gathering and can be replicated via text-to-image generators by simply appending the artist’s name to the prompt, e.g., “Create a dragon battling an ogre in the style of Greg Rutowski.”

He told the BBC, “The first month that I discovered it, I realised that it will clearly affect my career and I won’t be able to recognise and find my own works on the internet,” adding, “The results will be associated with my name, but it won’t be my image. It won’t be created by me. So it will add confusion for people who are discovering my works.”

He continued, “All that we’ve been working on for so many years has been taken from us so easily with AI.”

The last statement really hits the target, as AI’s reproduction of complex, talented works takes mere seconds, meaning not only do artists’ work become redundant, but the skills used to create them become lost.

Humanity’s loss of authentic skills and knowledge is one of AI’s most pressing risks, dubbed “enfeeblement,” illustrated by the Disney film WALL-E, where humans lose the ability to move because of technology.

Another artist who spoke out about AI reproducing their works is Kelly McKernan, an illustrator based in Tennessee who found that more than 50 pieces of her artwork had been listed as training data on Large-scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network (LAION).

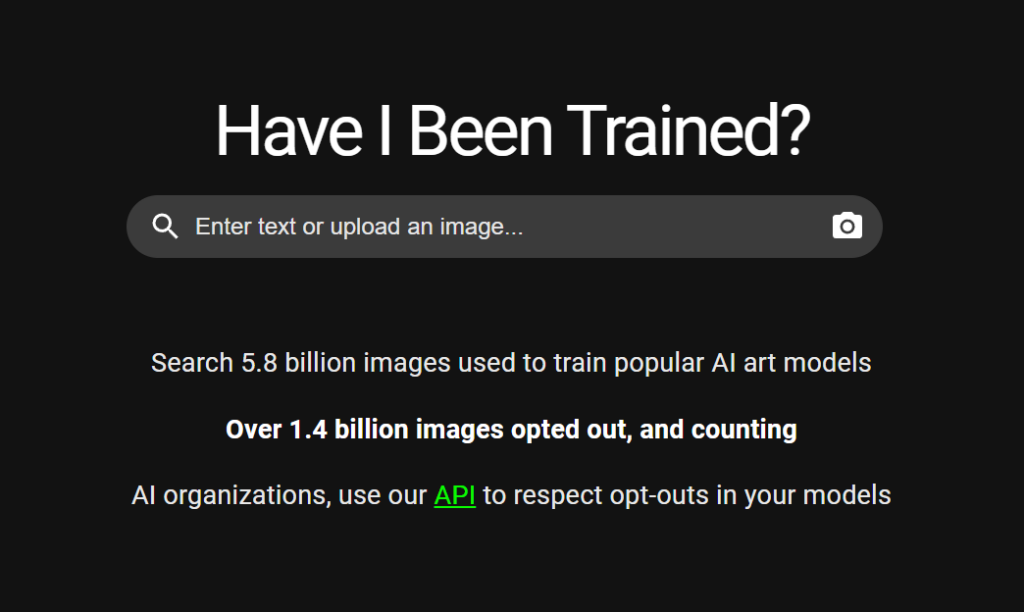

You can search some 5.8 billion images found in AI training sets with the tool “Have I Been Trained?” which is how McKernan stumbled upon her work.

LAION is a non-profit organization that creates open-sourced models and datasets, many of which have been used to train high-profile text-to-image models, including Stable Diffusion and Imagen.

“Suddenly all of these paintings that I had a personal relationship, and journey with, had a new meaning, it changed my relationship with those artworks,” McKernan said.

Legal battles are in progress

McKernan, joined by fellow artists Sarah Anderson and Karla Ortiz, has taken legal action against Stability AI, DeviantArt, and Midjourney.

Their lawsuit joins a tide of legal action against AI companies from both writers and visual artists.

Larger companies are also suing or planning to sue AI developers, including Getty Images, who claimed Stability AI had unlawfully copied and processed 12 million of its images without permission.

McKernan said, “As it is, copyright can only be applied to my complete image. I hope it [the lawsuit] encourages protection for artists so AI can’t be used to replace us. If we win, I hope a lot of artists are paid. It’s free labour and some people are profiteering from exploiting.”

McKernan’s style, seen below, has been requested in some 12,000 MidJourney prompts.

View this post on Instagram

A fundamental issue here is that copyright law was simply not built for the era of AI.

Liam Budd of the performing arts and entertainment union Equity argued for updated laws that reflect the potential business opportunities generative AI offers.

He stated, “We need more clarity in law and are campaigning for the Copyright Act to be updated.”

In response to the rising tide of AI-powered copyright infringement, various jurisdictions, such as the EU, have proposed that AI developers disclose any copyrighted material used for training.

Will that be enough? Have AI developers already shown they’ll likely get away with it?

After all, most of these datasets are assembled already, and AI companies could argue they’re merely updating models to circumvent the need to declare copyright material.

Do the lawsuits have sound legal footing?

This current round of class action lawsuits largely revolves around two arguments.

- First, the claim that the companies have infringed on artists’ copyrights by using their works without permission.

- Second, the allegation that the AI outputs are essentially derivative content due to their inclusion in the training data.

The application of these arguments differs worldwide, such as in the US, where ‘fair use’ laws are generally more liberal than in the EU. This further complicates the AI copyright landscape. If companies are operating in the UK, for instance, they may find it more challenging to argue ‘fair use.’

Additionally, generative AI firms are being sued, not the entities compiling the datasets, such as LAION in the case of MidJourney. Eliana Torres, an intellectual property lawyer with the law firm Nixon Peabody, points out that if LAION created the dataset, the alleged infringement occurred at that point, not when the dataset was used to train the models.

Then, proving that AI-generated works are reproductions of original works is challenging due to the AI’s complex nature, using algorithmic processing to break down and re-assemble images.

Regulatory bodies have been caught off guard by the legal implications of generative AI, and while interim solutions like automated filters and opt-out provisions for artists are being developed, they may not be sufficient.

Until judges reach verdicts on individual cases, which could take months, generative AI firms are exposing themselves to significant legal risks across many jurisdictions.

History indicates that copyright law can adapt to accommodate new technology, but until a consensus emerges, both artists and AI developers are very much in the dark.

Judges put the dampers on lawsuits

Thus far, judges have given artists little to be optimistic about.

For instance, US District Judge William Orrick cast doubt on the Kelly McKernan lawsuit.

According to Judge Orrick, McKernan and the other plaintiffs needed to “provide more facts” about the alleged copyright infringement and clearly differentiate their claims against each company (Stability AI, DeviantArt, and Midjourney).

Orrick noted the systems had been trained on “five billion compressed images,” so artists must provide stronger evidence that their works specifically were involved in the alleged copyright infringement. A website tracking this lawsuit has recently uploaded technical information about how these models work by interpolating content from images in their training set.

The case is being represented by the Joseph Saveri law firm, which is also representing at least 5 other similar cases against AI companies.

And again, copyright is potentially infringed upon data collection rather than generation.

Section 1202(b) of America’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act “is about identical ‘copies … of a work’ – not about stray snippets and adaptations,” – arguing that works are ‘copied’ by the AI model’s process is potentially flimsy.

Orrick’s views also raise questions about the liability of companies like MidJourney and DeviantArt, which incorporate Stable Diffusion technology from Stability AI into their own generative AI systems.

If AI developers, such as OpenAI, Meta, etc., are bestowed some liability for infringing artists’ copyrights, they’re vulnerable to further legal action.

Authors and writers are also launching litigation

In another recent lawsuit, US comedian and author Sarah Silverman and authors Christopher Golden and Richard Kadrey allege that their words were unlawfully used to train AI models like ChatGPT and LLaMA.

The lawsuit makes parallel claims to those lodged by visual artists, but this time, the AIs are trained on public text data.

The lawsuit alleges that ChatGPT was able to accurately summarize books such as Silverman’s “The Bedwetter,” Golden’s “Ararat,” and Kadrey’s “Sandman Slim.” Crucially, the level of detail supplied by the summaries can’t be explained by excerpts of the books uploaded on Wikipedia or bookstore websites.

The plaintiffs accuse OpenAI and Meta of using copyrighted books from “shadow libraries” without consent.

Shadow libraries, such as Bibliotik, Library Genesis, and Z-Library, house large quantities of illegally copied information.

While it’s apparent AI companies have monetized products with the assistance of copyrighted work, they have several layers of protection, including the inherently complex nature of their models and the idiosyncratic space they occupy in the moral, ethical, and legal landscape.

What do courts have to decide?

While regulators are still deliberating rules around AI, judges might have the first tilt at shaping the future copyright landscape.

This could result in a patchwork of legislation confined by the specifics of each case and the jurisdiction it was ruled in.

Currently, there are many questions to answers, including:

Q1: Does training a model on copyrighted material require a license?

- Fair use vs. licensing: Courts may have to decide whether the temporary copying of data during training falls under “fair use,” which would permit the usage without a license. This could depend on factors like the purpose of the copying, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and the effect on the copyrighted work’s market value.

- International perspectives: Different jurisdictions might have different stances on this matter. For example, the EU’s Copyright Directive might be interpreted differently from the U.S. Copyright Act.

Q2: Does generative AI output infringe on copyright for the materials on which the model was trained?

- Determining derivative work: Is the generative output simply a transformation, or does it actually create a derivative work that infringes copyright? This question might require a complex analysis of similarity and creativity.

- Liability issues: If there is infringement, who is liable? The creator of the AI? The user of the AI? The distributor?

Q3: Does generative AI violate restrictions on removing, altering, or falsifying copyright management information?

- Specific cases: Analysis of specific algorithms like Stable Diffusion might be necessary to determine if generated works could accidentally reproduce or manipulate watermarks or other copyright information.

- Intention vs. accidental infringement: The courts may need to determine whether there was an intention to remove or alter copyright information or if it was an unintentional consequence of the AI’s operation.

Q4: Does generating work in the style of someone violate that person’s rights?

- Defining the right of publicity: The right of publicity varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Courts may have to interpret whether creating works in someone’s style is tantamount to using their likeness or identity.

- Commercial vs. non-commercial use: The application might differ depending on whether or not the AI’s outputs are used for commercial gain.

Q5: How do open-source licenses apply to training AI models and distributing the resulting output?

- Understanding open source licensing: Courts may need to determine how open source licenses apply to AI training data and generated outputs.

Right now, we’re missing one thing: a ruling. Right now, it’d be folly to predict whether gratuitous data scraping will remain acceptable. If creators find a chink in the AI industry’s legal armor, the damage could be sizeable. But it’s looking like a big if.

Once rulings start filtering through and we come closer to regulation coming into effect, the future direction of AI should become clearer – until the next set of challenges, that is.