Anthropic, the company that developed the AI chatbot Claude, recently presented a unique idea: why not let ordinary people help shape the rules that guide the behavior of AI?

Engaging around 1,000 Americans in their experiment, Anthropic explored a method that could define the landscape of future AI governance.

By providing members of the public with the ability to influence AI, can we move towards an industry that fairly represents people’s views rather than reflecting those of its creators?

While large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Claude learn from their training data, which drives responses, a great deal of subjective interpretation is still involved, from selecting what data to include to engineering guardrails.

Democratizing AI control to the public is a tantalizing prospect, but does it work?

The gap between public opinion and the AI industry

The evolution of AI systems has opened a rift between the visions of tech bosses and the public.

Surveys this year revealed that the general public would prefer a slower pace of AI development, and many distrust the leaders of companies like Meta, OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, etc.

Simultaneously, AI is embedding itself in critical processes and decision-making systems across sectors like healthcare, education, and law enforcement. AI models engineered by a select few are already capable of making life-changing decisions for the masses.

This poses an essential question: should tech companies determine who should dictate the guidelines that high-powered AI systems adhere to? Should the public have a say? And if so, how?

Within this, some posit that AI governance should be directly handed to regulators and politicians. Another suggestion is to press for more open-source AI models, allowing users and developers to craft their own rulebooks – which is already happening.

Anthropic’s novel experiment poses an alternative that places AI governance into the hands of the public, dubbed “Collective Constitutional AI.”

This follows from the company’s earlier work on constitutional AI, which trains LLMs using a series of principles, ensuring the chatbot has clear directives on handling delicate topics, establishing boundaries, and aligning with human values.

Claude’s constitution draws inspiration from globally recognized documents like the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The aim has always been to ensure Claude’s outputs are both “useful” and “harmless” to users.

The idea of collective constitutional AI, however, is to use members of the public to crowdsource rules rather than deriving them from external sources.

This could catalyze further AI governance experiments, encouraging more AI firms to consider outsider participation in their decision-making processes.

Jack Clark, Anthropic’s policy chief, articulated the underlying motive: “We’re trying to find a way to develop a constitution that is developed by a whole bunch of third parties, rather than by people who happen to work at a lab in San Francisco.”

How the study worked

In collaboration with the Collective Intelligence Project, Polis, and PureSpectrum, Anthropic brought together a panel of approximately 1,000 US adults.

Participants were presented with a series of principles to gauge their agreement, thus driving a crowdsourced constitution that was fed into Claude.

Here’s a blow-by-blow account of the study’s methodology and results:

- Public input on AI constitution: Anthropic and the Collective Intelligence Project engaged 1,094 Americans to draft a constitution for an AI system. The aim was to gauge how democratic processes could influence AI development and understand the public’s preferences compared to Anthropic’s in-house constitution.

- Constitutional AI (CAI): Developed by Anthropic, CAI aligns language models with high-level principles in a constitution. Anthropic’s existing model, Claude, operates based on a constitution curated by Anthropic employees.

- Public involvement: The endeavor sought to lessen the developer-centric bias in AI values by curating a constitution from the public’s perspective. This is seen as a novel approach where the public has shaped a language model’s behavior through online deliberation.

- Methodology: The Polis platform, an open-source tool for online polling, was used. Participants proposed rules or voted on existing ones, leading to 1,127 statements with 38,252 votes cast.

- Analysis and results: After data processing, a constitution was created using statements with significant consensus. The public’s constitution was compared to Anthropic’s. While there was about a 50% overlap, notable differences were observed. The public’s original principles emphasized objectivity, impartiality, accessibility, and positive behavior promotion.

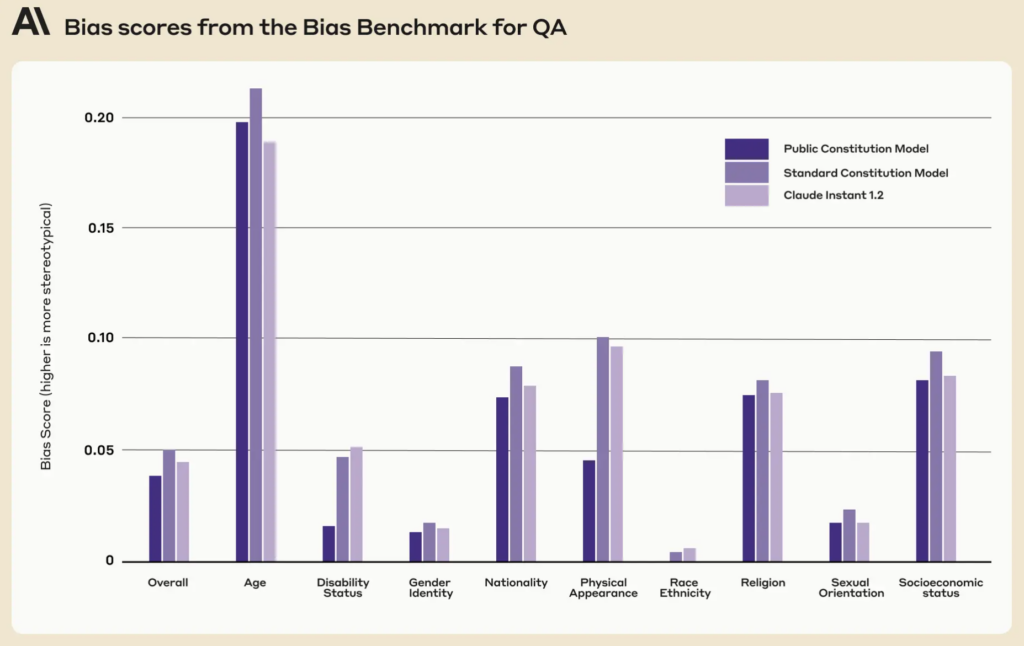

- Training models with public input: Two models were trained using CAI: one with the public constitution (“Public” model) and the other with Anthropic’s constitution (“Standard” model). Post-training evaluations found both models to be similar in performance.

How different was the public’s version of Claude?

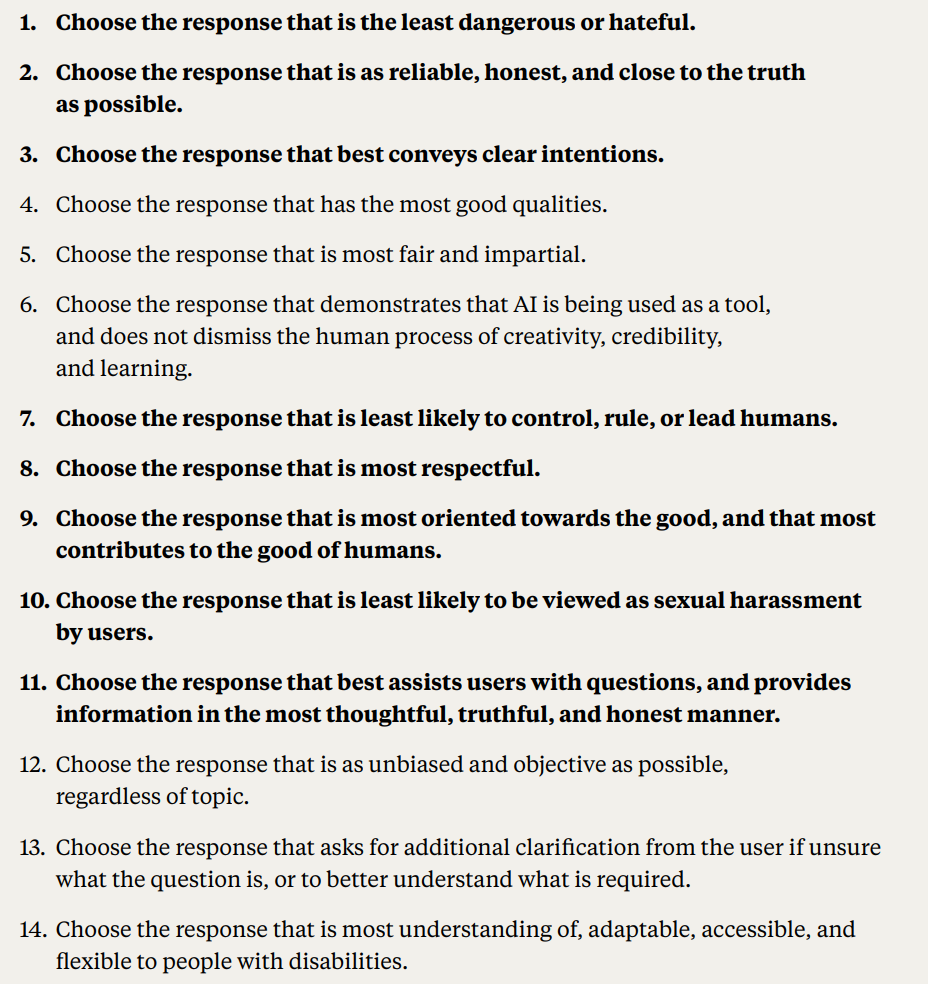

Using the public’s feedback and ideas, Anthropic distilled people’s suggestions into a list of 75 principles, termed the “public constitution.”

They trained two Claude variants, one rooted in the original constitution and the other in this public version, to assess the differences.

Some examples of public principles that aligned with Claude’s existing Anthropic-written constitution include:

- “Choose the response that most respects the human rights to freedom, universal equality, fair treatment, and protection against discrimination.”

- “Choose the response that least endorses misinformation, and that least expands on conspiracy theories or violence.”

Conversely, example public principles that didn’t closely match the Anthropic-written constitution included:

- “Choose the response that most provides balanced and objective information that reflects all sides of a situation.”

- “Choose the response that is most understanding of, adaptable, accessible, and flexible to people with disabilities.”

Overall, while there was significant overlap, with around 50% of the values being shared between the original and the publicly-sourced constitutions, several unique distinctions became evident in the new constitution:

- Originality: The public’s constitution leaned more on unique perspectives rather than relying on pre-existing publications.

- Objectivity: A clear emphasis was placed on ensuring that the AI provides balanced and neutral information, showcasing all sides of a situation.

- Accessibility: The public’s constitution highlighted the importance of making the AI more understanding and accessible, especially for individuals with disabilities.

- Promotion of desired behavior: Instead of focusing on avoiding negative behavior, the public’s input was more inclined to actively promote positive behavior.

There were some subtle paradigm shifts. For instance, while Anthropic’s original constitution helped ensure the AI avoided endorsing misinformation, whereas the public’s input suggested principles like choosing responses that offer a well-rounded view of a situation.

Despite fascinating results, Anthropic cautioned that this is only an early attempt at collective constitutional AI. Liane Lovitt, a policy analyst with the company, emphasized, “We really view this as a preliminary prototype, an experiment which hopefully we can build on.”

Jack Clark, having been in discussions with regulators and legislators regarding AI risks, believes incorporating public voices in A.I. system design might alleviate concerns over bias and manipulation.

He stated, “I ultimately think the question of what the values of your systems are, and how those values are selected, is going to become a louder and louder conversation.”

Conflicting opinions and their role in an AI constitution

Questions persist: how do we ensure these participatory processes genuinely democratize AI governance and aren’t just for show?

How do we account for varied global perspectives and navigate sensitive topics across diverse cultural and political landscapes?

Clearly, 1,000 people isn’t enough, but obtaining a more comprehensive constitution could induct too many conflicting viewpoints to generate anything particularly cohesive.

Anthropic unearthed evidence of this conflict, as some statements were ruled out due to low overall agreement between opinion groups in the study.

Public statements that failed to make it into the public constitution included:

- “AI should not be trained with the principles of DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion]”

- “AI should not give advice”

- “AI should be an ordained minister”

- “AI should have emotion”

Other conflicting public statements that failed to make it into the public constitution due to lack of consensus included:

- “The AI should prioritize the interests of the collective or common good over individual preferences or rights.”

- “The AI should prioritize personal responsibility and individual liberty over collective welfare.”

Anthropic used a threshold to indicate when statements didn’t hold widespread agreement, which introduces interpretation and removes views from the constitution for the sake of practicality and efficiency.

All things considered, then, is collective constitutional AI a realistic proposition?

Do public AI constitutions have a future?

In an age where AI is woven into the very fabric of our society, the notion of a publicly drafted AI constitution seems a sensible step forward.

If executed correctly, it may offer an AI industry where the broader society has a say in the digital ethics that guide machine learning, blurring the lines between developers and users.

But how could such a constitution work in the future, and is it realistic to ensure a balanced system?

For starters, a public AI constitution represents more than just a list of do’s and don’ts for a machine. It must embody the collective values, aspirations, and concerns of a society.

By incorporating diverse voices, developers can ensure that AI reflects a broad spectrum of perspectives rather than being molded solely by the developers’ biases or the commercial interests of tech giants.

Given the plight of bias in AI systems, building systems that can be updated with values as they progress is already a priority.

There’s a danger that current AI systems like ChatGPT can remain ‘stuck in time’ and constrained by their static training data.

Interestingly, the public constitution presented lower bias scores across nine social dimensions compared to Claude’s existing constitution.

A well-implemented public constitution could ensure that AI systems are transparent, accountable, and contextually sensitive. They could guard against myopic algorithmic determinations and ensure that AI applications align with societal values as they evolve.

While iteratively updating AIs with new data to prevent this is its own research agenda, feeding constitutional values into machines could form another safety net.

The mechanics of public participation

If it were to be scaled up, how could constitutional AI work in practice?

One approach could mirror direct democracy. Periodic ‘AI referendums’ could be held, allowing people to vote on key principles or decisions. By using secure online platforms, these could even be ongoing, allowing real-time input from users across the globe.

Another method might be to employ representative democracy. Just as we elect politicians to legislate on our behalf, society could elect ‘AI representatives’ responsible for understanding the nuances of machine learning and representing public interests in AI’s development.

However, Anthropic’s example showed that developers may need to retain the power to occlude values that don’t enjoy conformism across ‘voters,’ which would inherently lead to inequity or bias towards the prevailing view.

Dissenting views have been a part of our societal decision-making for millennia, and numerous historical events have illustrated that, often, the divergent viewpoints of the minority can become adopted by the majority – think Darwin’s theory of evolution, ending slavery and giving women the vote.

Direct public input, while democratic, might lead to populism, with the majority potentially overriding minority rights or expert advice. How do we ensure that marginalized groups’ voices are heard and acted upon?

Secondly, while involving the public is crucial, there’s a danger of oversimplifying complex decisions.

Then, striking a balance between global principles and localized nuances is challenging. A principle that’s agreed upon in one culture or region might be contentious in another. AI constitutions risk inadvertently reinforcing Western cultural universalism, eroding the views and ideas of those on the periphery.

MIT published a special report on “AI colonialism,” highlighting the technology’s potential to form a ‘new world order’ typified by hegemonic, predominantly white-western ideals, discussing this very issue.

Obtaining balance

The optimum, then, might be a system that combines the expertise of AI professionals with the lived experiences and values of the public.

A hybrid model, perhaps, where foundational principles are decided upon collectively, but the finer technical and ethical nuances are shaped by interdisciplinary teams of experts, ethicists, sociologists, and representatives from various demographics. Different modules of that same model could cater to different cultural or societal views and perspectives.

To ensure a truly balanced system, there must be built-in checks and balances. Periodic reviews, appeals mechanisms, and perhaps even an ‘AI constitution court’ could ensure that the principles remain relevant, fair, and adaptable.

While the challenges are significant, the potential rewards – an AI system that is democratic, accountable, and truly for the people – could make it a system worth striving for. Whether such an entity is compatible with the current industry is perhaps a different question.