When ChatGPT rolled out to the masses, it ignited the imagination of millions of students worldwide.

Let’s face it – many would testify that finding ways to cut corners without sacrificing results is part of the education experience. Generative AI takes that to a whole new level.

There was probably a honeymoon period when generative AI circulated between students, but teachers didn’t know much about it.

Asking ChatGPT to write an essay and watching it spurt out thousands of words in mere seconds must have felt like a dream come true – especially the night before a deadline.

Since generative AI surfaced in the mainstream, the education system has grappled with the technology, with some establishments lurching to ban it entirely and others looking to embed it into their processes.

Debates surrounding AI’s role in education are far from confined to that industry – they concern the very fabric of human knowledge.

AI for academic writing: no magic bullet, yet

ChatGPT is far from perfect for academic work, with a tendency to falsify references, provide bogus examples, and misinterpret essential concepts.

Once you experience its cunning first-hand, you won’t forget it.

While using ChatGPT to help research a report on type 2 diabetes, I caught the output fabricating a longitudinal population study in Taiwan with some 10,000 participants.

The bogus study was provided complete with quotes, convincing data, and even an academically formatted reference ready for copying straight into my research.

Upon following up on the study, it quickly became apparent that it simply did not exist in any form. There was one similar study from 2000, but it bore very few similarities to what ChatGPT created.

I’ve tested the process of requesting academic references from ChatGPT numerous times, and it’s always proved highly vulnerable to fabricating virtually anything that requires a degree of specificity.

This made me think…if I were a teacher, the first place I’d check to gauge the authenticity of my students’ work would be the references.

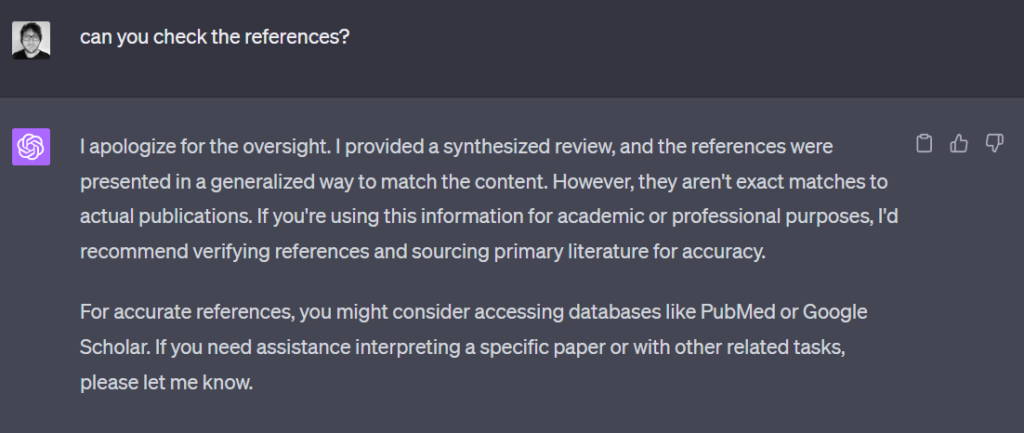

ChatGPT’s references look exceptionally convincing, and while it’s often correct when referencing high-profile well-cited research, it’s quickly caught out by anything venturing into obscurity. ChatGPT will admit that it provides a ‘generalized review’ to ‘match the content,’ prompting you to check the references directly.

Of course, not all essays require academic referencing, but in school settings with younger students, teachers are more likely to understand the nuances of their students’ writing, whereas there’s a greater distance between students and educators at higher levels.

If a student is fabricating their references, then they aren’t reading them – and therein lies the potential of AI to erode critical thinking, which is central to learning.

Writing in a 2023 compilation of 43 expert opinions published in the International Journal of Information Management, Sven Laumer from Scholler-Endowed Chair of Information Systems, Institute of Information Systems Nürnberg, Germany, discussed how AI has reinforced the importance of critical analysis.

He writes, “When it comes to college essays, it’s more crucial that we teach our students to ask important questions and find ways to answer them.”

“This is the intellectual core that will benefit both the students and society. Therefore, we should place a greater emphasis on teaching critical thinking skills and how to add value beyond AI.”

Writing in the same article, Giampaolo Viglia from the Department of Economics and Political Science, University of Aosta Valley, Italy, concurred.

Viglia argues, “The advent of ChatGPT – if used in a compulsive way – poses a threat both for students and for teachers. For students, who are already suffering from a lower attention span and a significant reduction in book reading intake the risk is going into a lethargic mode.”

What are the risks of replacing our own critical analysis with the analysis presented to us by AI?

Enfeeblement at the hands of AI

AI’s ability to conduct the ‘heavy lifting’ is finely balanced with its ability to replace all lifting, leading to enfeeblement – the ultimate impact of humanity’s reliance on technology.

The Disney film WALL-E has become a well-touted example of enfeeblement, with obese, immobile humans floating about in spaceships as robots serve their every whim.

In WALL-E, the effects of technology’s impacts are primarily depicted as physical, but AI poses a potentially more nightmarish scenario by governing our thought processes or even making our decisions for us.

Dr. Vishal Pawar, a Dubai-based neurologist, suggests that excessive use of AI might render certain brain functions, especially those tied to detail orientation and logical reasoning, redundant. This could impact how we utilize our intellectual capacities.

He suggests that overusing tools like ChatGPT might weaken neural pathways linked to critical thinking, impacting the brain’s frontal lobe. “The most frequent memory issue I encounter is a lack of attention,” he states.

However, such risks contrast with AI’s ability to fuel the pursuit of knowledge, as demonstrated by advances in science and medicine, where machine learning (ML) enables humans to laser-focus their skills on where they have the most significant impact.

Researchers are using AI to explore space, map biological systems, model the climate in increasing detail, and discover new drugs, all in a fraction of the time it would take to perform that work manually.

To uphold these advantages, AI has to be harnessed as an additive to human intelligence – an extension – rather than a replacement.

Can AI’s influence over education be halted?

Some might be familiar with a tool named Turnitin, used by educational establishments worldwide to detect evidence of plagiarism by identifying strings of words copied from other sources.

Now, Turnitin and other plagiarism detectors have a considerably more complex task on their hands – identifying AI-generated content. That’s proving to be an intractable task.

Yves Barlette from the Montpellier Business School (MBS), Montpellier, France, highlights that AI hasn’t just become proficient at circumventing AI detectors but also suffers from a high false-positive rate.

She says, “For example, a student may have a particular writing style that resembles AI-generated text. It is therefore, important to find legally acceptable solutions, especially when it comes to punishing or even expelling students who cheat.”

This has been proven in experimental research, with one study showing that essays written by non-English native speakers were falsely flagged as AI-generated almost half of the time, with one particular AI detector producing an absurd 98% false positive rate.

AI is imperfect, AI detectors can’t be relied upon, and preventing students from using generative AI is unrealistic.

There is perhaps no option but to establish new models and pathways for learning.

As Tom Crick, Professor of Digital & Policy at Swansea University, UK, describes, “Education has been incorporating and reimagining the threats and possibilities of technology for decades; AI will likely be no different but will require not only a technological shift but also a mindset and cultural shift.”

So, how do we go about it?

Generative AI offers a new model for learning

The intersection of generative AI and education is precipitating a subtle yet profound shift in the learning process.

In many ways, AI signals continuity from previous technological advancements, such as the calculator and internet, something discussed by both OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang.

Huang said now was the best time to graduate, likening the AI boom to the release of the personal computer (PC) in the 80s.

Historically, the conventional classroom placed the student as a passive recipient, absorbing information transmitted by an instructor.

Technology has equipped students with more self-guided learning tools, and with the advent of generative AI, they’re now taking on the role of active seekers that can explore and interrogate vast knowledge at their fingertips.

This signals an epistemological transition never seen before in human history.

Epistemology – the study of knowledge – describes traditional education as grounded in a ‘transmission’ epistemology, where knowledge is seen as a static entity passed from teacher to student.

In this traditional model, the path of learning is largely linear, moving from ‘ignorance’ to ‘enlightenment.’

Generative AI could usher forward an ‘active seeker’ model, where knowledge isn’t just transmitted from one to another but is actively constructed by the learner.

The student, aided by AI, becomes the navigator, discerning relevance, contextualizing insights, and weaving together understandings from a plural of sources.

Active information seekers know where to look for information and how to interrogate it – the latter being vital in harnessing AI as a learning tool without entirely investing in its outputs.

AI is a biased institution, but aren’t they all?

AI has a deep-seated bias problem, partly because the internet has a bias problem.

In the age of the internet, society often outsources thinking to big tech by assuming search engine results are transparent and non-partisan when they likely aren’t.

Plus, the practice of search engine optimization (SEO) and pay-per-click (PPC) advertising means top search results are not always positioned on the quality of their information – though this has improved massively in the last decade or so.

Further, while AI is liable to falsehoods and misinformation, so are traditional teaching institutions.

Numerous famous teaching establishments are renowned for their social and political leanings. You can even find compilations of “the most conservative colleges” in the USA, which include universities like Liberty University in Virginia, which gained a reputation for teaching creationism over evolutionary biology.

In the UK, Oxford and Cambridge – collectively known as Oxbridge – were once known for their political leanings, albeit this varies between their colleges.

On the flip side, other educational establishments are known to be decidedly left-wing, and higher education tutors tend to be predominantly left-leaning in the UK, at least.

There are gender and race biases in educational institutions, too, with women under-featuring in higher education teaching and research – an imbalance also inherited by AI.

While this doesn’t necessarily create a biased dissemination of knowledge, education is always liable to subjectivities in various forms – as is AI.

Recent studies into AI bias found GPT models to be predominantly left-leaning and Meta’s LLaMA to be more right-leaning.

While the bias of AI systems doesn’t absolve traditional educational systems of their prejudices and vice versa, the solution is similar in both cases: emphasize critical thinking and pursue equality measures to achieve representative systems of knowledge.

Critical thinking in the age of AI

In time, and with critical engagement in educational settings, AI’s ‘active seeking’ model could push the burden of responsibility of ensuring balance and accuracy to the student.

With the technology’s capacity to generate seemingly endless streams of information, the onus of verifying knowledge’s accuracy, relevance, and context falls heavily on the seeker.

Then, educators can shift their role to teaching critical thinking, analysis, and verification while contributing their own human insights and opinions to what essentially becomes a generative encyclopedia or textbook.

Fostering critical learners in the age of AI could yield wider benefits, not just for scrutinizing the output of large language models (LLMs) and their liabilities, but for developing critical opinions elsewhere in society.

As Sven Laumer said, “This is the intellectual core that will benefit both the students and society.”

Researchers and educators Nripendra P Rana, Jeretta Horn Nord, Hanaa Albanna, and Carlos Flavian write, “If we want our students to learn how to solve real time problems, we need to come out of the traditional teaching model of simply delivering the one-way theoretical knowledge to students and go beyond that to make tools like ChatGPT a friend in the classroom ecosystem that is not something to fear.”

“It should rather be used to encourage such technology as a medium for transforming practical education. Further, it could be of great help to students as they acquire life learning skills and use them in their future careers to solve actual problems at their workplaces.”

Humanity has been saddled with AI’s benefits and drawbacks, and it’s our responsibility to shape the technology under our stewardship.

There are few foregone conclusions at this stage, and people are already thinking critically about AI, which is a positive sign.

Teaching students how to critically engage with this new learning medium without using it compulsively is paramount to shaping our collective futures.

Ultimately, AI is an additive tool that extends our abilities rather than replaces them, and we must keep it this way.