Our ancestors once huddled in small, isolated communities, their faces illuminated by flickering fires.

Evidence of controlled campfires for cooking and warmth dates back some 700,000 years, but thousands of years before then, Homo erectus had started living in small social groups.

At this point, we can observe changes in the vocal tract, which indicate primitive forms of communication.

This is when early humans began to translate and share their internal states, essentially building a primitive worldview in which someone, and something, existed beyond the self.

Early forms of communication and social bonding brought about a cascade of changes that thrust human evolution forward, culminating in the formation and dominance of modern humans, Homo sapiens.

Little did early hominids know that the fire around which they gathered was but a pale reflection of the fire that burned within them – the fire of consciousness illuminating them on the path to becoming human.

And little did they know that countless generations later, their descendants would find themselves gathered around a different kind of fire – the bright, electric glow of their screens.

The primal roots of human thought

To understand the nature of this primitive mind, we must look to the work of evolutionary psychologists and anthropologists who have sought to reconstruct the cognitive world of our distant ancestors.

One of modern evolutionary psychology’s key insights is that the human mind is not a blank slate but a collection of specialized cognitive modules shaped by natural selection to solve specific adaptive problems.

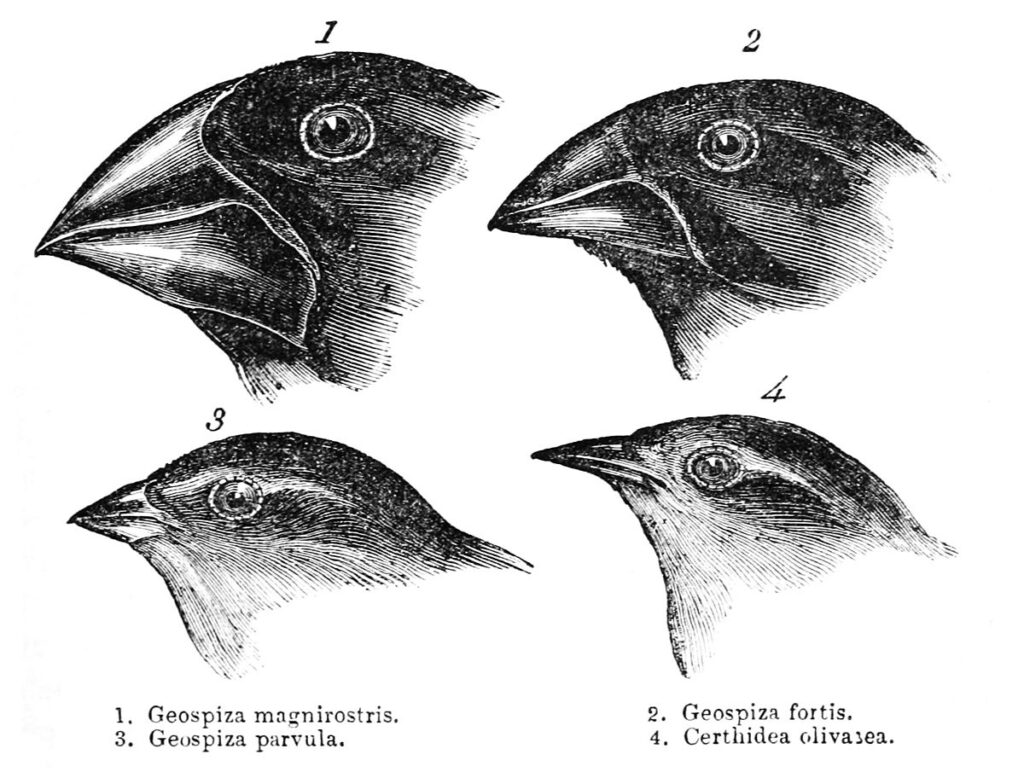

This is not exclusive to humans. Darwin’s early research observed that the Galapagos finches, for example, shared highly specialized beaks that enabled them to occupy different ecological niches.

These varied tools correlated with diverse behaviors. One finch might crack nuts with its large, broad beak, whereas another might pry berries from a bush using its razor-like bill.

As psychologist Leda Cosmides and her colleagues, including Steven Pinker, have argued in theories now summed as ‘evolutionary psychology,’ the brain’s modules once operated largely independently of one another, each processing domain-specific information.

In the context of primitive history, this modular architecture would have been highly adaptive.

In a world where survival depended on quickly detecting and responding to threats and opportunities, a mind composed of domain-specific modules would have been more efficient than a general-purpose brain.

Our distant ancestors inhabited this world. It was a world of immediate sensations, primarily unconnected by an overarching narrative or sense of self.

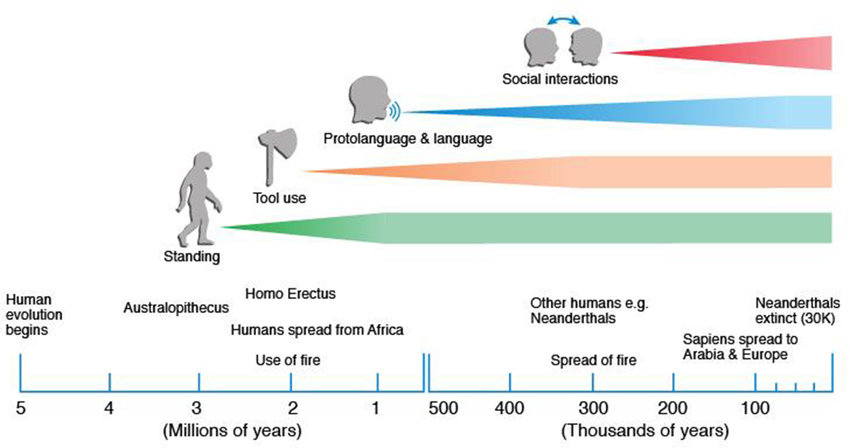

However, over the course of thousands of years, hominid brains became more broadly interconnected, enabling tool use, protolanguage, language, and social interaction.

Archaeological evidence suggests that it wasn’t until the last 20,000 years or so that humans began to ‘settle down’ and engage in complex societal and cultural practices.

Today, we know that different structures within the brain become heavily integrated from birth. fMRI studies, such as Raichle et al. (2001), show that information is continually shared between various parts of the brain at rest.

While we take this for granted and probably can’t imagine anything else, it wasn’t the case for our ancient ancestors.

For example, Holloway’s research (1996) on early hominid brains indicates changes in brain architecture over time supported enhanced integration. Stout and Chaminade (2007) explored how tool-making activities correlate with neural integration, suggesting that building tools for different purposes may have driven the development of more advanced neural capability.

The need for complex communication and abstract reasoning increased as humans progressed from small-scale groups where individuals were intimately familiar with one another’s experiences to larger groups that included people from varied geographies, backgrounds, and appearances.

Language was perhaps the most powerful catalyst for humanity’s cognitive revolution. It created shared meaning by encoding and transmitting complex ideas and experiences across minds and generations.

Moreover, it conferred a survival advantage. Humans who could efficiently communicate and work with others gained advantages.

And, gradually, humans started to vocalize and communicate just because rather than for any specific adaptive or survival value.

Entering the age of hyper-personalized realities

It took humans millions of years to move from isolated groups to larger, more interconnected societies.

Today, we might face a strange inversion of this trend — a return to more individualized worlds mediated by AI and VR technologies.

In 2016, Mark Zuckerberg strode through an event as attendees donned the Meta 2 headset, the resulting image becoming an iconic forwarding of VR’s perils to isolate people in their personal worlds.

is this picture an allegory of our future ? the people in a virtual reality with our leaders walking by us. pic.twitter.com/ntTaTN3SdR

— Nicolas Debock (@ndebock) February 21, 2016

Today’s VR headsets, led by the Apple Vision Pro, can generate highly realistic and context-aware text, images, and 3D models for endlessly personalized immersive environments, characters, and narratives.

In parallel, recent breakthroughs in edge computing and on-device AI processing have enabled VR devices to run sophisticated AI algorithms locally without relying on cloud-based servers.

This embeds real-time, low-latency AI applications into VR environments, such as dynamic object recognition, gesture tracking, and speech interfaces.

It’s now possible to create virtual worlds not just superficially tailored to our tastes but fundamentally shaped by our cognitive quirks and idiosyncrasies.

We become not just content consumers but active participants in our own private realities.

So what about the impacts? Is it all just a novelty? Will the hype break as people grow bored of VR as they did a few years ago?

We don’t know yet, but VR product sales are definitely picking up pace. And while the Vision Pro has flaws and remains prohibitively expensive – at a cool $3,499 – this will change.

Even so, asserting that everyone will live in VR within five, ten or even 25 years is not sensible. VR has had plenty of hype moments that dissolved away.

Meta is evidence of that. According to Bloomberg, they invested $50 billion into its Metaverse project, which ultimately resulted in one of its biggest commercial failures.

However, the Apple Vision Pro has the potential to succeed where Meta fell short. The Vision Pro’s advanced technology, intuitive controls, and seamless integration with Apple‘s ecosystem address many shortcomings that hindered Meta’s project.

From the iPhone to the Apple Watch, Apple has consistently demonstrated its ability to create compelling products that resonate with consumers and compel broad adoption.

The timing of Apple‘s entry into the VR market is favorable. AI doesn’t just support VR performance-wise; it also helps conjure a futuristic world where VR truly belongs.

Spotting people in public spaces with headsets is becoming more frequent, symbolising the technology’s growing momentum.

VR’s impact on the brain

So, what about the impacts of VR? Is it just a visual tonic for the senses, or should we anticipate deeper impacts?

There’s plenty of preliminary evidence. For example, a study by Madary and Metzinger (2016) argued that VR could lead to a “loss of perspective,” potentially affecting an individual’s sense of self and decision-making processes.

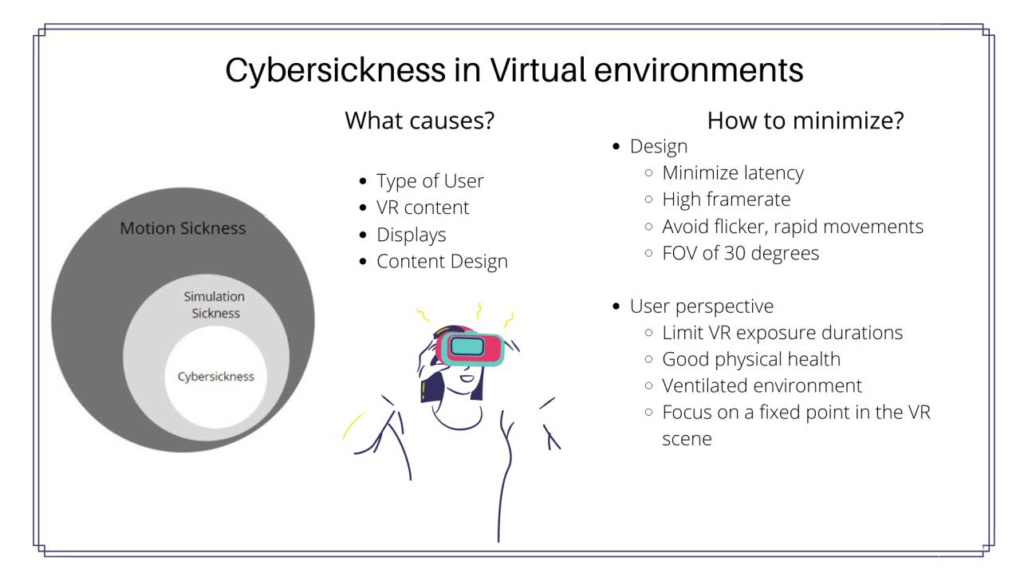

A systematic review by Spiegel (2018) examined VR use’s potential risks and side effects. The findings suggested that prolonged exposure to VR environments could lead to symptoms such as eye strain, headaches, and nausea, collectively called “cybersickness.”

Among the stranger impacts of VR, a study by Yee and Bailenson (2007) explored the concept of the “Proteus Effect,” which refers to the phenomenon where an individual’s behavior in a virtual environment is influenced by their avatar’s appearance.

The study found that participants assigned taller avatars exhibited more confident and assertive behavior in subsequent virtual interactions, demonstrating the potential for VR to alter behavior and self-perception.

We’re sure to see more psychological and medical research on prolonged VR exposure now the Apple Vision Pro is out.

The positive case for VR

While it’s important to acknowledge and address the risks associated with VR, it’s equally crucial to recognize this technology’s benefits and opportunities.

One of the most promising applications of VR is in education. Immersive virtual environments offer students interactive learning experiences, allowing them to explore complex concepts and phenomena in ways that traditional teaching methods cannot replicate.

For example, a study by Parong and Mayer (2018) found that students who learned through a VR simulation exhibited better retention and knowledge transfer than those who learned through a desktop simulation or slideshow. That could be a lifeline for some with learning difficulties or sensory challenges.

VR also holds massive potential in the realm of healthcare, particularly in the areas of therapy and rehabilitation.

For example, a meta-analysis by Fodor et al. (2018) examined the effectiveness of VR interventions for various mental health conditions, including anxiety disorders, phobias, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Another intriguing study by Herrera et al. (2018) investigated the impact of a VR experience designed to promote empathy toward homeless individuals.

The Apple Vision Pro has already been used to host a personalizable interactive therapy bot named XAIA.

Lead researcher Brennan Spiegel, MD, MSHS, wrote of the therapy bot: “In the Apple Vision Pro, we are able to leverage every pixel of that remarkable resolution and the full spectrum of vivid colors to craft a form of immersive therapy that’s engaging and deeply personal.”

Avoiding the risks of over-immersion

At first glance, the prospect of living in a world of hyper-personalized virtual realities may seem like the ultimate fulfillment of a dream – a chance to finally inhabit a universe that is perfectly tailored to our own individual needs and desires.

It might also be a world we can live in forever, saving and loading checkpoints as we roam digital environments perpetually.

However, left unchecked, there’s another side to this ultimate form of autonomy.

The notion of “reality” as a stable and objective ground of experience depends on a common perceptual and conceptual framework, a set of shared assumptions, categories, and norms that allow us to communicate and coordinate our actions with others.

If we become enveloped in our individualized virtual worlds where each individual inhabits their own bespoke reality, this common ground might become increasingly fragmented.

When your virtual world radically differs from mine, not just in its surface details but in its deepest ontological and epistemological foundations, mutual understanding and collaboration risk fraying at the edges.

That oddly mirrors our distant ancestors’ isolated, individualized worlds.

As humanity spends more time in isolated digital realities, our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors may become more attuned to their own unique logic and structure.

So, how can we adopt the advantages of next-gen VR without losing sight of our shared humanity?

Vigilance, awareness, and respect will be critical. The future will see some who embrace living in VR worlds, augmenting themselves with brain implants and cybernetics, and so on. It will also see those who reject that favor a more traditional lifestyle.

We must respect both perspectives.

This means being mindful of the algorithms that mediate our interactions with the world and actively seeking experiences that challenge our assumptions and biases.

Hopefully, keeping one foot outside of the virtual world will become intuitive.

If it doesn’t, today’s communal technologies may serve to drive us apart rather than bring us together like the fire of old.