Luke Farritor, a 21-year-old computer science student from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, has revealed the text inside a carbonized scroll from ancient Herculaneum.

This scroll has been unreadable since the volcanic eruption in AD 79 that also engulfed Pompeii. Farritor’s machine learning algorithm successfully pinpointed Greek letters on the rolled-up papyrus, including the word πορϕυρας (porphyras), which means ‘purple.’

His technique hinged on identifying minor, nuanced differences in surface texture to train his neural network to detect ink, and in turn, leterring.

“When I saw the first image, I was shocked,” said Federica Nicolardi, a papyrologist from the University of Naples. “It was such a dream,” she continued, “I can actually see something from the inside of a scroll.”

The scrolls, buried by Mount Vesuvius’s eruption in AD 79, have remained largely inaccessible due to their fragile state.

Manually unrolling the charred scrolls causes them to flake apart, leading scholars to fear that the contents would remain a mystery forever.

As Nicolardi explained, “These are such crazy objects. They’re all crumpled and crushed.”

Recognizing the challenge of deciphering the scrolls, the Vesuvius Challenge was set up, offering various awards, including a grand prize of US$700,000 for deciphering multiple passages from a scroll.

On 12 October, it was announced that Farritor had clinched a prize of $40,000 for identifying over 10 characters in a small section of the papyrus.

Another participant, Youssef Nader from the Free University of Berlin, received $10,000 for second place.

Historian of ancient Greece and Rome, Thea Sommerschield, described the ability to finally discern letters and words inside the scrolls as “extremely exciting.”

Sommerschield mentioned that interpreting these could “revolutionize our knowledge of ancient history and literature” from the region.

It’s not the first time researchers have attempted to read these ancient carbonized scrolls. In 2019, Brent Seales, a Professor of Computer Science specializing in virtual reading and preservation of ancient scrolls, attempted to “virtually unwrap” the scrolls using X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans.

In 2016, Seales succeeded with an ancient Hebrew parchment found in 1970 at Ein Gedi, Israel, unveiling parts of the Book of Leviticus.

However, the Herculaneum scrolls posed a different challenge: the ink, made of charcoal and water, didn’t stand out in the scans.

This is where Farritor succeeded by focusing on a specific subtle texture, coined ‘crackle,’ for traces of ink.

Farritor said, “I was jumping up and down,” after his algorithm revealed five letters from a newly-released segment. “Oh my goodness, this is actually going to work,” he realized.

Shortly thereafter, he refined his model and identified the requisite ten letters for the prize, with the word ‘purple’ not previously identified in the Herculaneum scrolls.

The grand prize of the Vesuvius Challenge is yet to be unveiled, with a deadline set for 31 December.

AI for decoding ancient languages

Six millennia ago, the Sumerians settled in Mesopotamia, the land spanning the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

This region, covering present-day Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey, and Syria, witnessed the evolution from small agrarian communities to grand urban civilizations. Cities like Uruk blossomed, integrating intricate canals, irrigation frameworks, and governance hubs. It was a critical era for the progress and evolution of humanity.

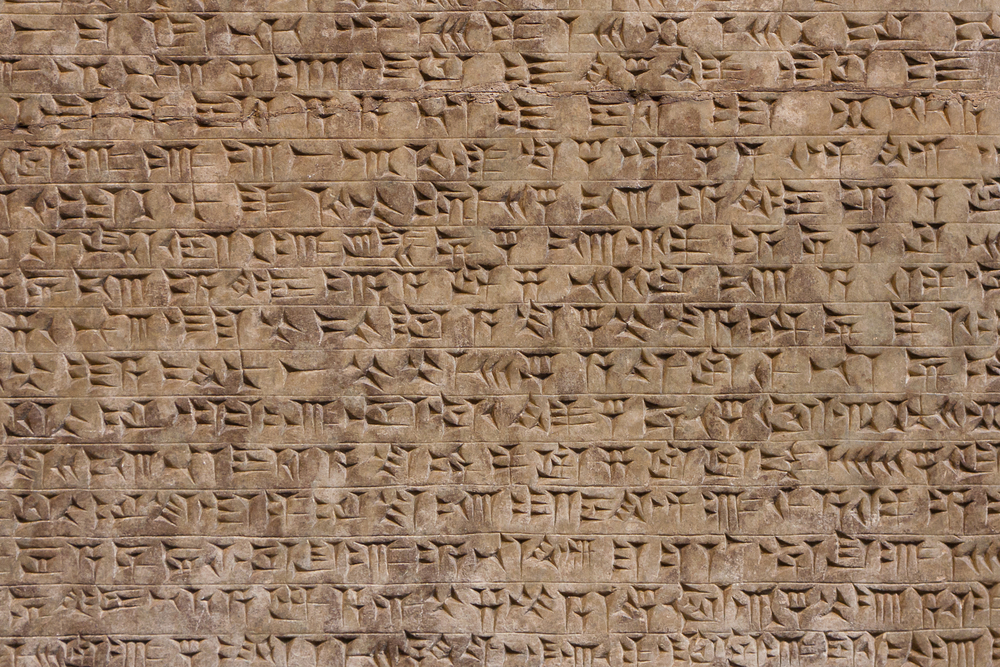

The Sumerians wrote in a script known as cuneiform. This writing system required pressing reeds into clay, generating complex logo-syllabic inscriptions. Cuneiform is not a language – it’s a script encompassing some 15 languages over three millennia.

While cuneiform scripts were primarily used as administrative tools for tasks like recording livestock or transactions, by 2700 BC, a wide range of more philosophical and creative writings emerged.

One of the most notable of these writings is the Epic of Gilgamesh, which sprawls across twelve tablets.

Enrique Jiménez from Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich states, “Half of human history lies encapsulated in these cuneiform tablets.”

However, a mere 75 individuals, as per New Scientist, can decode cuneiform despite tens of thousands of untranslated tablets worldwide.

Machine learning is now helping researchers unravel the stories etched into stone tablets, helping them fill gaps and order the texts chronologically to discover more about how the ancient Sumerians lived.

Machine learning’s role in ancient text decryption

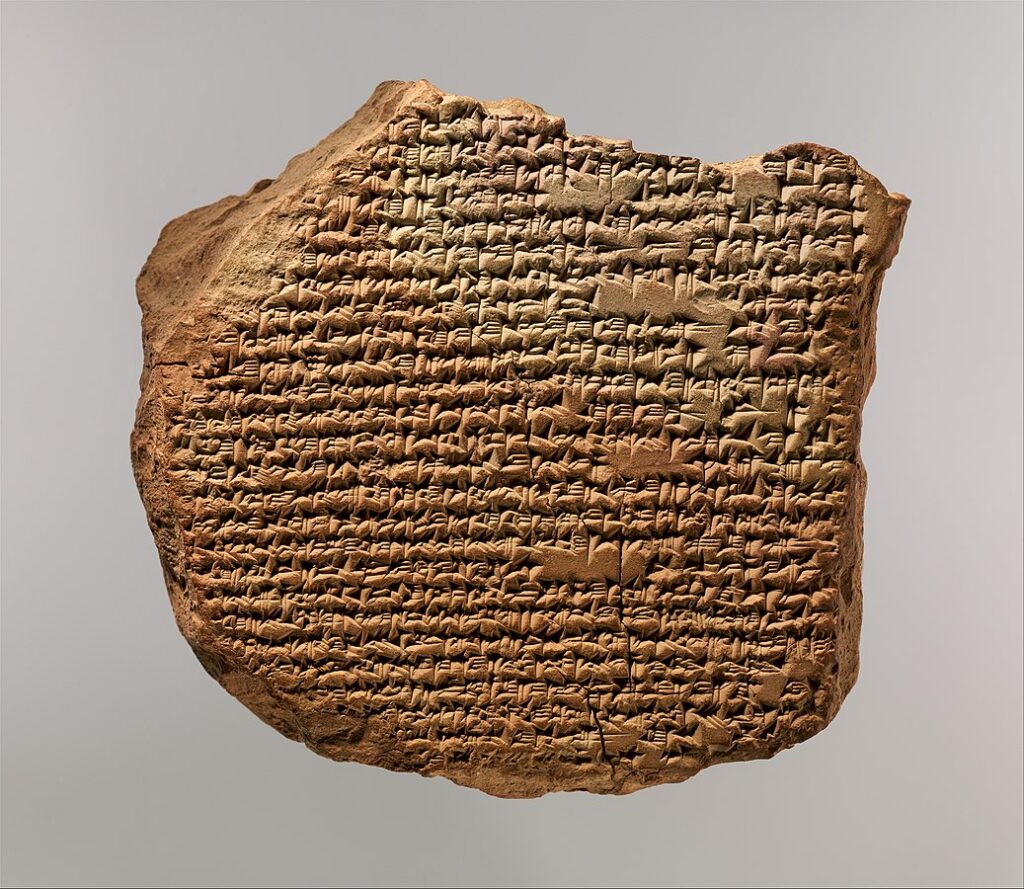

Enrique Jiménez and has team founded the Electronic Babylonian Literature, a collaboration between archaeologists, data scientists, and historians.

To analyze cuneiform tablets, the team used a machine learning technique originally designed for gene sequence comparison. This AI predicts the content of missing sections and the boundaries at which fragments align.

This technique led to discoveries like missing sections of the Epic of Gilgamesh and a newfound Mesopotamian genre describing educational parodies and jokes for children.

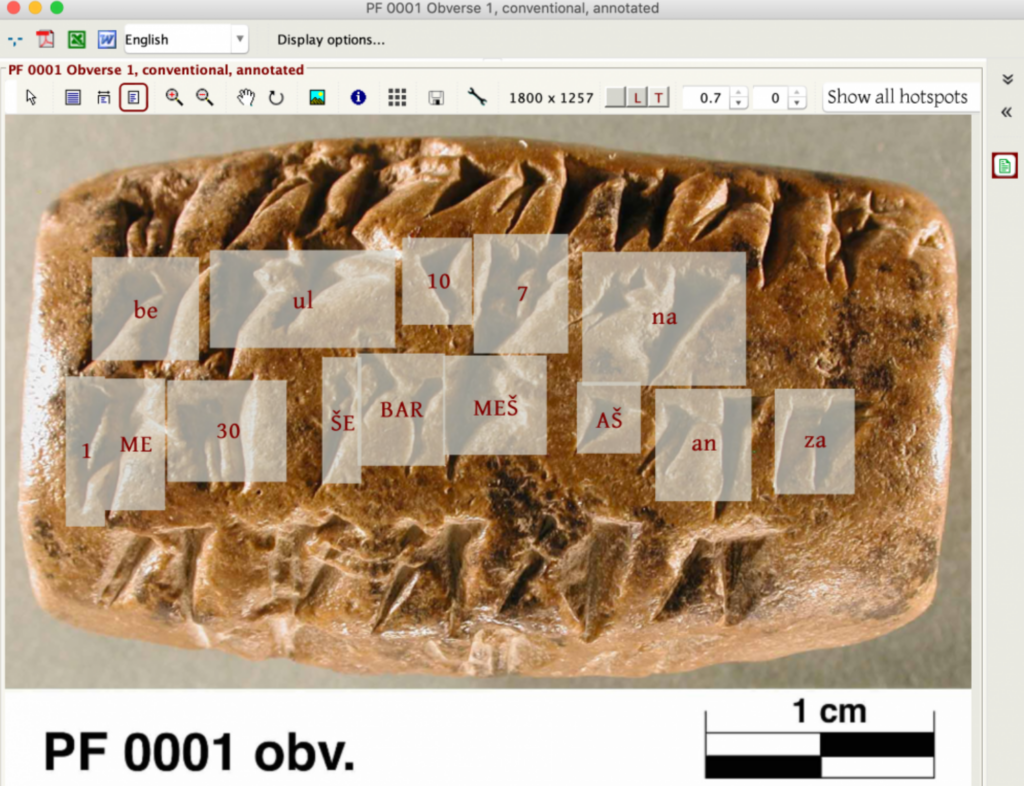

In 2020, a separate model, DeepScribe, was trained on 6,000 annotated images from the Persepolis Fortification Archive, which specifies approximately 100,000 symbols from the Elamite language (from modern-day Iran), dated around 500 BC.

Leveraging resources from the UChicago Research Computing Center, Krishnan, and Eddie Williams trained a model capable of decoding these signs with an impressive 80% accuracy.

The team intends to develop DeepScribe into a versatile deciphering tool, retrainable for languages other than Elamite.

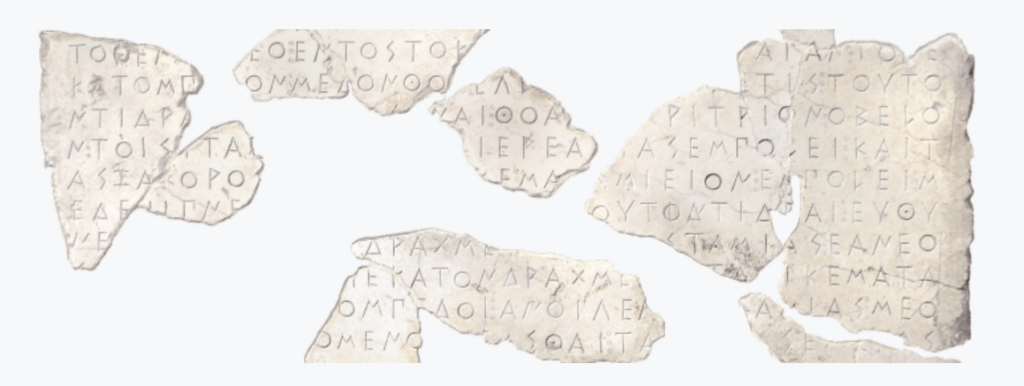

DeepMind has also investigated decoding ancient languages using machine learning – in this case, damaged Ancient Greek tablets.

Named Ithaca, this model restored texts with 72% precision, approximated their age within three decades, and even surmised their origin with 71% accuracy.

Ithaca’s training involved 60,000 texts from 700 BC to AD 500, tagged with data about their time and place across 84 ancient territories.

The intersection of ancient texts and cutting-edge AI showcases how even millennia-old mysteries are not immune to the advancements of modern technology.

By blending the old with the new, researchers are both preserving history and chartering previously unknown archeological knowledge.

These breakthroughs underscore the limitless possibilities when we merge human curiosity with technological prowess, proving that there’s a new lens through which to view the wonders of our collective past.