In his influential essay “What Happened to the Future?”, Peter Thiel lamented that society had moved away from a vision of the future filled with “flying cars,” focusing instead on incremental advancements such as the “140 characters” of a Twitter post. Has AI changed that?

Thiel’s comments were published in 2011 when AI was still a somewhat fringe technology used primarily for scientific and research purposes.

Since then, AI has surged into the limelight, and humanity has started dreaming of a new AI-powered future, a future of trepidation and excitement – a future of unknowns.

AI challenges Thiel’s criticism of the technology industry, reinvigorating both utopic and dystopic visions of the future.

So, is the future back? What does it look like now?

Back to the 70s

The year was 1969. The Cold War had met its peak, and the Space Race was approaching a critical mass as the US and Russia close in on the Moon.

On July 20th, 1969, shortly after 10:51 EST, one of history’s most iconic phrases beamed to 650 million TV sets worldwide, “…one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

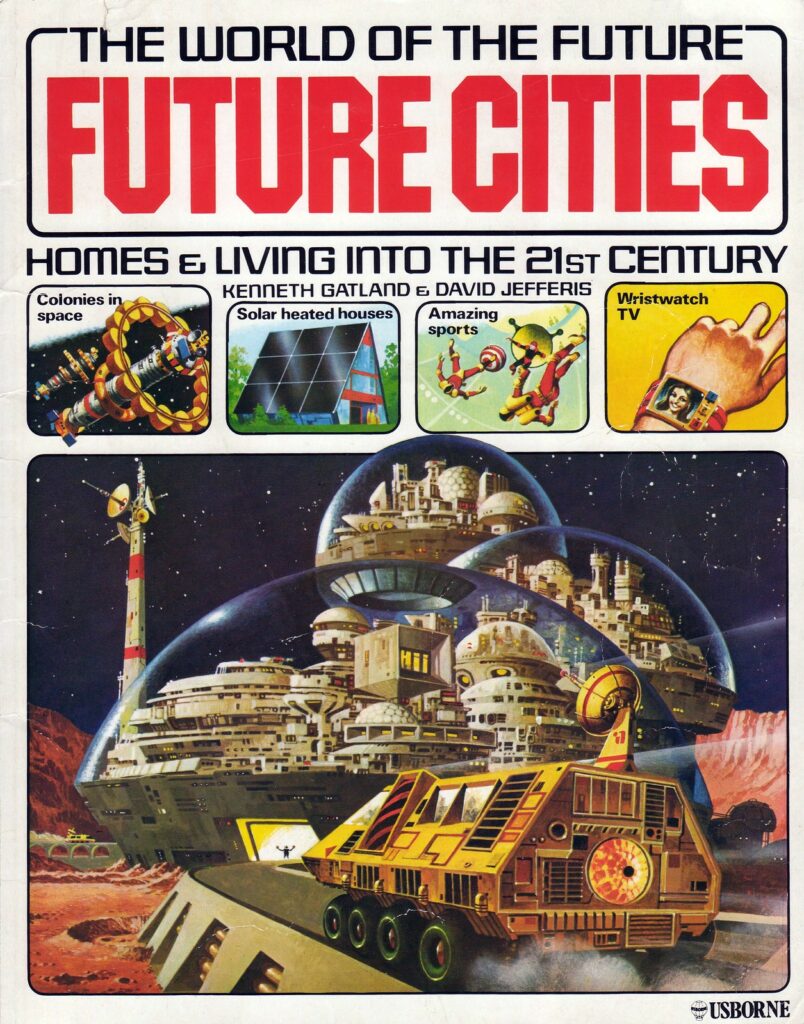

The future had arrived. The 1970s signaled a futurist awakening, triggering publications such as the Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth and a series of works by elite scientists, including Princeton physicist Gerard K. O’Neill and MIT researcher Eric Drexler, who hashed out blueprints for everything from nanotechnology to space colonialism.

David Valentine, professor of anthropology at The University of Minnesota, wrote, “The 1970s was also the period when “the future”—dystopian or utopian, fixed by forecasts but open to technological manipulation—seemed to most fully capture the imaginations of the lay public, politicians, policy makers and forecasters.”

The emergence of AI

AI’s origins date back to the 1950s when computer scientists John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky hosted the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (DSRPAI) in 1956.

This very event saw the birth of the term “artificial intelligence.” 8 years later, in 1964, an MIT researcher, Joseph Weizenbaum, created the first chatbot – ELIZA – the forerunner to modern language AIs like ChatGPT. In 1966, AI pioneer Martin Minsky tasked a student to connect a camera to a computer and “have it describe what it sees” – the first description of what we now call computer vision (CV).

At first, AI was largely neglected by the scientific community, except for a small group of scientists that believed in its potential. In 1970, Minsky told Life Magazine, “From three to eight years, we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.”

As we now know, Minsky’s timing was way off. Investment in AI wasn’t forthcoming, and the technology was grossly held back by a lack of computing power.

This period of stagnant development was dubbed the “AI winter.” One of McCarthy’s students, Hans Moravec, stated that “computers were still millions of times too weak to exhibit intelligence.”

It was a period of technological disenchantment – humans had discovered so much in a short period and were left with a deluge of ideas but not enough time or money to explore them.

“We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters”

Peter Thiel, the co-founder of PayPal, has often discussed this technological plateau, encapsulated in his widely circulated quote, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

This dichotomy illustrates the death of ‘the future’ at the hands of digital technology. His main argument is that venture capital began to favor ‘incremental change’ or even ‘fake technologies,’ which had little tangible or intrinsic value but made a lot of profit in a short space of time. Thiel and his colleagues wrote, “We believe that the shift away from backing transformational technologies and toward more cynical, incrementalist investments broke venture capital.”

Of course, there were some incredible inventions in the 80s and 90s, no less the internet. But even so, Thiel argues that technology transitioned from novel technologies or inventions to digital products and services.

All the best engineers were too busy tweaking Facebook and Google apps rather than inventing technologies like flying cars.

Thiel questioned, “Are there any real technologies left? Have we reached the end of the line, a sort of technological end of history? Once every last retailer migrates onto the Internet, will that be it? Is the developed world really developed, full stop?”

Others jumped on the bandwagon and echoed the sentiment. For example, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) wrote in 2019, “Men landed on the moon 50 years ago, a tremendous feat of American creativity, courage, and, not least, technology. The tech discoveries made in the space race powered innovation for decades. But I wonder, 50 years on, what the tech industry is giving America today.”

Thiel on AI

Thiel’s essay directly references AI: “True general artificial intelligence represents the highest form of computing…machine learning also represents another compelling opportunity, with the potential to create everything from more intelligent game AIs to Watson. While we have the computational power to support many versions of AI, the field remains relatively poorly funded.”

In 2011, when the comments were published, AI investment stood at around $12nb, according to Statista. In 2021, it stood at almost $100bn, and some analysts believe the market will grow twenty-fold by 2030, reaching $2tn.

As Thiel notes, the computational power is there, and now, the money is there, too.

Does AI prove Thiel wrong when he says, “Are there any real technologies left? Have we reached the end of the line, a sort of technological end of history?”

…Is the future back?

We’ve entered a nascent period of technological innovation – we simply don’t know the extent to which AI will change our world.

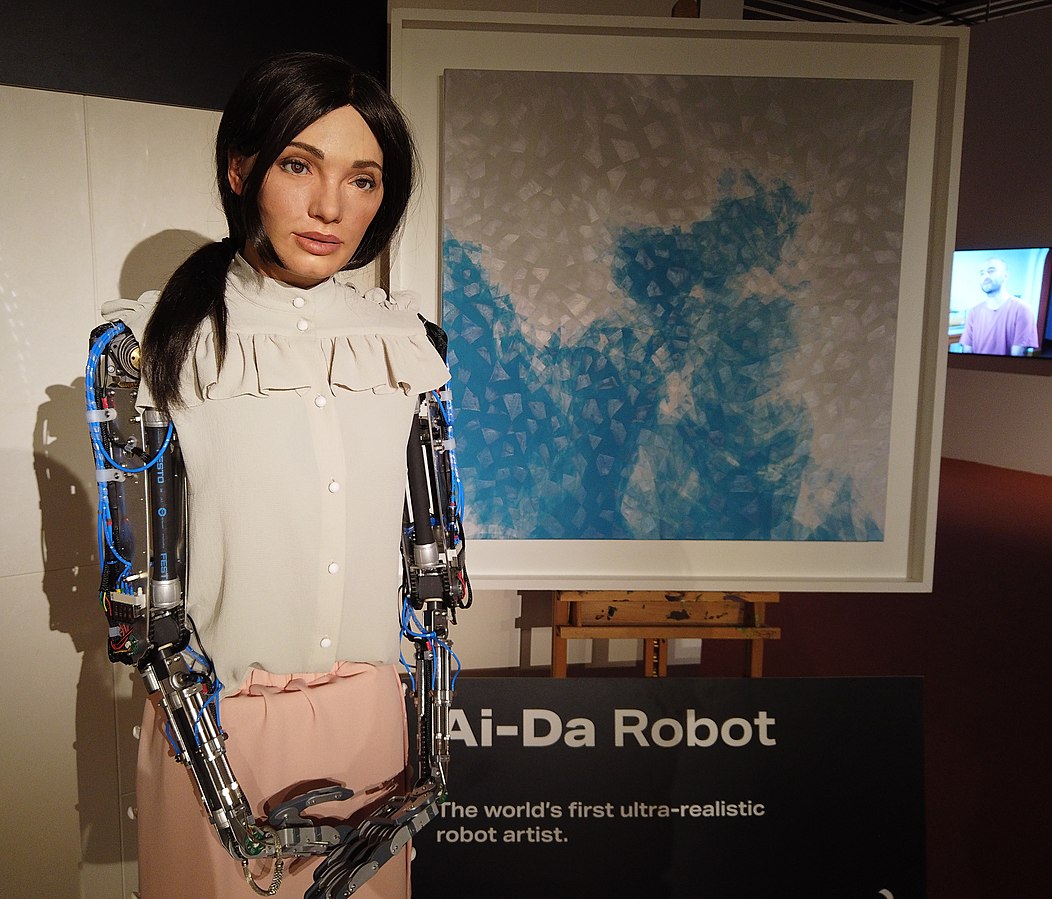

AI is unique in that it straddles the digital technologies Thiel criticizes and the novel inventions he encourages. From exoskeletons that facilitate walking in paralyzed individuals to robots that create and exhibit their own art, AI is a digital technology that can be implanted into practically anything.

In addition to AI’s incredibly far-ranging talents, it has a certain omnipresence that sets it apart from other technologies. AI lives in web browsers, it lives in phones, it lives in robots, it lives in vehicles. And it’s growing more intelligent by the day, with some arguing ‘superintelligent’ AI, or artificial general intelligence (AGI), that exceeds human cognition, is just a few years away.

This raises an important question. Right now, humans decide what technologies to develop with AI, but what happens if it becomes too intelligent or autonomous enough to defy us? What if it learns to remove itself from technologies, adapt to different conditions, or even self-replicate?

In recent months, AI leaders, technologists, public figures, and politicians have been stating their stance on AI, and it’s fair to say that dystopian narratives are causing the biggest stir.

Notable critics include two of AI’s ‘godfathers,’ Yoshua Bengio and Geoffrey Hinton, who administered stark warnings about AI risks such as weaponization and loss of control. The other, Yann LeCun, believes they’re vastly overblown.

To intensify the debate, the Center for AI Safety recently published a statement on AI risk, signed by 350 tech leaders, including the CEOs of Google DeepMind, OpenAI, and, Anthropic, as well as Bill Gates, numerous academics, and esteemed researchers, politicians, and public figures.

Fox, CNN, CBS, the BBC, and other mainstream news networks have thrust AI to the fore of public debate, igniting our imaginations of a futuristic scenario where machines take over.

Indeed, this imagined world already lives inside of us in the form of I, Robot, Matrix, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metropolis, the Matrix, Terminator, Ex Machina, WALL-E, and other futuristic AI-infused films that have one thing in common: it doesn’t end well for humanity.

AI’s pros and cons balance on a knife edge

We hear a lot about AI’s risks, perhaps because they make the most sensational stories.

AI’s enormous potential must be harnessed and focused on key applications, from slowing climate change to disease prevention and medical rehabilitation, agricultural optimization, and transportation.

There are amazing examples of these technologies helping people right now, from grassroots projects in Africa focused on eradicating agricultural disease to providing cheap MRI scans and discovering new drugs that tackle antibiotic-resistant bacteria. AI might create futures for people where they did not exist before.

AI remains embryonic – we must ensure it grows into something that creates rather than destroys. While we still have time, humanity must steer AI for the benefit of humanity.

We may be living in the future once again, and it remains in our hands – for now, at least.