AI companies are pushing for regulation. Is their motivation paranoia or altruism? Or does regulation secure competitive goals?

In early May, Luke Sernau, a senior software engineer at Google, wrote an informal memo about open-source AI. It was widely circulated on Google’s internal systems before a consulting firm, Semi-Analysis, verified and published it.

Here are some excerpts:

“We’ve done a lot of looking over our shoulders at OpenAI. Who will cross the next milestone? What will the next move be?

But the uncomfortable truth is, we aren’t positioned to win this arms race and neither is OpenAI. While we’ve been squabbling, a third faction has been quietly eating our lunch. I’m talking, of course, about open source.

Plainly put, they are lapping us. Things we consider “major open problems” are solved and in people’s hands today. While our models still hold a slight edge in terms of quality, the gap is closing astonishingly quickly.

Open-source models are faster, more customizable, more private, and pound-for-pound more capable. They are doing things with $100 and 13B params that we struggle with at $10M and 540B. And they are doing so in weeks, not months.

At the beginning of March, the open source community got their hands on their first really capable foundation model, as Meta’s LLaMA was leaked to the public.

It had no instruction or conversation tuning, and no RLHF. Nonetheless, the community immediately understood the significance of what they had been given. A tremendous outpouring of innovation followed, with just days between major developments…

Here we are, barely a month later, and there are variants with instruction tuning, quantization, quality improvements, human evals, multimodality, RLHF, etc., etc., many of which build on each other. Most importantly, they have solved the scaling problem to the extent that anyone can tinker.

Many of the new ideas are from ordinary people. The barrier to entry for training and experimentation has dropped from the total output of a major research organization to one person, an evening, and a beefy laptop.”

Sernau’s memo was picked up by major news outlets and sparked debate around whether big tech’s push for regulation masks a motive to force open-source AI out of the game. Ben Schrekcinger from Politico writes, “open-source code is also more difficult to ban since new instances can pop up if regulators attempt to shut down a website or tool that uses it. Combined with other decentralizing features, these open-source projects have the potential to disrupt not just Silicon Valley’s business model, but the governance models of Washington and Brussels.”

The open-source AI community is already thriving. Developers are solving challenges in days that take Google and OpenAI months or years. Sernau argues that agile communities of open-source developers are better equipped to build iterate models than big tech, as they’re more diverse, efficient, and pragmatic.

If this is the case, big tech’s dominance over AI could be fleeting.

The Meta LLaMA leak

Meta’s LLaMA model, a large language model (LLM) like ChatGPT, was leaked on 4chan a week after the company sent out access requests. On March 3rd, a downloadable torrent appeared on the messaging forum and spread like wildfire.

As Sernau indicates, the open-source community proceeded to modify LLaMA, adding impressive functionality without enterprise computer resources.

Building powerful AI models is cheaper than ever, and open-source communities are pushing to democratize access. While LLaMA is a largely pre-trained model, other open-source models, like BLOOM, were trained by volunteers.

Training BLOOM required a supercomputer equipped with 384 NVIDIA A100 80GB GPUs which was luckily donated by the French government. The open-source AI company Together recently announced $20m seed funding, and AI-focused cloud providers like CoreWeave offer hardware below-market rates.

Open-source projects have various means of focusing resources and outflanking big tech. Big tech would probably like us to think their AIs are the product of decades of work and billions of dollars in investment – the open-source community probably disagrees.

On the topic of big tech segregating themselves from smaller AI projects, at an event in India, former Google executive Rajan Anandan asked OpenAI CEO Sam Altman whether Indian engineers could build foundational AI models with a $10m investment.

Altman responded, “It’s totally hopeless to compete with us on training foundation models. You shouldn’t try, and it’s your job to like trying anyway. And I believe both of those things. I think it is pretty hopeless.”

But, in his memo, Sernau expresses that open-source is already competing with big tech. He says, “Holding on to a competitive advantage in technology becomes even harder now that cutting edge research in LLMs is affordable. Research institutions all over the world are building on each other’s work, exploring the solution space in a breadth-first way that far outstrips our own capacity.”

Open-source developers are building alternatives to big tech’s AIs and overtaking them in performance and user statistics.

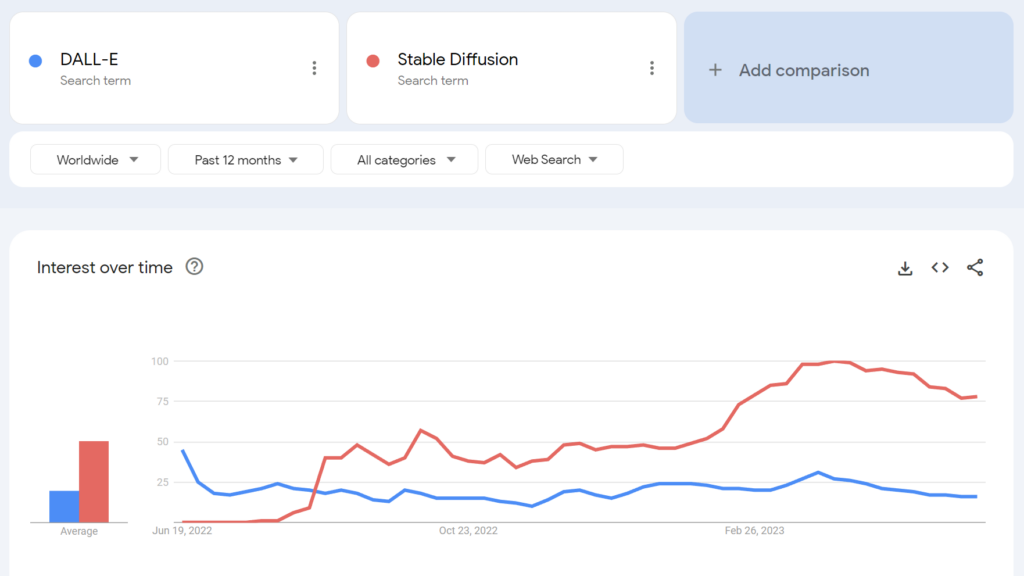

For example, the open-source Stable Diffusion became more popular than OpenAI’s DALL-E within months of its launch.

To what extent can we pry apart potential ulterior motives here? Does big tech’s regulatory push have any altruistic merit?

The open-source AI community

Besides LLaMA, there are at least three major examples of open-source AI projects:

- Hugging Face & BLOOM – The AI firm Hugging Face collaborated with over 1,000 volunteer scientists to develop BLOOM, an open-source LLM. BLOOM aims to offer a more transparent and accessible counterpart to proprietary AI models.

- Together – An AI startup named Together has successfully raised $20 million in seed funding to support its objective of building decentralized alternatives to closed AI systems. They unveiled several open-source generative AI initiatives, including GPT-JT, OpenChatKit, and RedPajama.

- Stability AI – In April 2023, Stability AI, the company behind Stable Diffusion, launched StableLM, a sequence of open-source alternatives to ChatGPT.

It’s worth noting that while some of these developers (e.g., Stable Diffusion) offer their models via intuitive, easy-to-use dashboards, others, such as BLOOM, require significant resources to run. For starters, you need around 360 GB of RAM to run BLOOM, but there are many nifty tricks to bring resource requirements down.

As AI-capable hardware comes down in price and open-source models become simpler to deploy, it’s quite possible that virtually anyone could deploy models similar to ChatGPT. The Google memo leak cites examples of people tuning and deploying LLaMA on consumer devices, including a MacBook.

For businesses with significant IT resources, open-source models save money and provide data sovereignty and control over training and optimization.

However, not everyone is optimistic about the impact of powerful open-source AI. For example, cybersecurity researcher Jeffrey Ladis tweeted, “Get ready for loads of personalized spam and phishing attempts,” and “Open sourcing these models was a terrible idea.”

AI proliferation makes us all less safe. Seems like a good thing to prevent, and also a pretty difficult challenge!

I would not be that surprised if a state actor managed to get ahold of the OpenAI’s frontier models in the next year or two https://t.co/PUEWvfUFqk

— Jeffrey Ladish (@JeffLadish) May 10, 2023

Another observer tweeted, “Open source is a threat but not in the way you think. It’s a threat because AI in the hands of people who can use it for their own ends becomes even harder to regulate or keep track of, and that’s a bigger problem.”

Google and OpenAI claim they’re scared of open source AI, there’s “no moat” between them all. But it’s not really true.

Open source is a threat but not in the way you think. It’s a threat because AI in the hands of people who can use it for their own ends becomes even harder to… pic.twitter.com/g6kMh3TshY

— Theo (@tprstly) May 5, 2023

Yann LeCun, often considered an ‘AI godfather’ alongside Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshio Bengman, argues the contrary, “Once LLMs become the main channel through which everyone accesses information, people (and governments) will *demand* that it be open and transparent. Basic infrastructure must be open.”

LeCun also dissented from mainstream narratives about AI risks, “I think that the magnitude of the AI alignment problem has been ridiculously overblown & our ability to solve it widely underestimated.” Elon Musk hit back in the Twitter thread, saying, “You really think AI is a single-edged sword?”

You really think AI is a single-edged sword?

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) April 1, 2023

Other commenters drew parallels between AI regulation and cryptography, where the US government tried to ban public cryptographic methods by classing them as “munitions” – dubbed the “Crypto Wars.”

Now, virtually everyone has the right to use encryption – but that battle was hard won – as could be the case with open-source AI.

OpenAI’s alienation of open-source AI

Open source is more than just software, code, and technology. It’s the principle, mindset, or belief that a cooperative, open, and transparent work environment outshines competition in a closed market.

OpenAI, once a non-profit company focused on public cooperation and open-source development, has steadily departed from its namesake.

The startup transitioned to a ‘for-profit’ company in 2019, effectively ending the company’s relationship with the open-source community. Investment from Microsoft disengaged OpenAI from any sort of ‘open’ R&D activities.

In mid-May, the company announced an open-source model in the pipeline, but they’ve not been forthright with the details.

Now, OpenAI is pushing for regulation that would hit emergent AI companies the hardest, not to mention potentially criminalizing the open-source community.

This has led some to criticize OpenAI’s push for regulation as nothing more than business – the business of protecting their profitable models from open-source communities seeking to democratize AI.

Is open-source AI a risk to big tech?

The combination of Google’s leaked memo, big tech’s push for regulation, and Altman’s denigration of grassroots AI projects raise a few eyebrows. Indeed, the legitimacy of AI’s risks – which justify regulation – has been questioned.

For example, when the Center for AI Safety (CAIS) published its seismic statement on AI risk, co-signed by multiple AI CEOs, some external observers weren’t convinced.

In a selection of expert reactions to the statement published by the Science Media Centre, Dr. Mhairi Aitken, Ethics Research Fellow at the Alan Turing Institute, said:

“Recently, these claims have been coming increasingly from big tech players, predominantly in Silicon Valley. While some suggest that is because of their awareness of advances in the technology, I think it’s actually serving as a distraction technique. It’s diverting attention away from the decisions of big tech (people and organisations) who are developing AI and driving innovation in this field, and instead focusing attention at hypothetical future scenarios, and imagined future capacities of AI.”

Some argue that big tech has the firepower to dedicate resources to ethics, governance, and monitoring, enabling them to shake off the worst of regulation and continue selling their products.

However, it’s simultaneously problematic to denounce AI risks as fantasy and claim there’s no value in regulation.

There are skeptics in both camps

Dismissing AI risks as purely speculative could prove a critical error for humanity.

Indeed, commenters with no conflict of interest have warned about AI for decades, including the late Professor Stephen Hawking, who said AI “could spell the end of the human race” and be the “worst event in the history of our civilization.”

While some may argue big tech is wielding visions of an AI apocalypse to reinforce market structures and raise barriers to entry, that does not eclipse the legitimacy of AI risks.

For instance, AI research teams have already proven AI’s ability to autonomously establish emergent goals with potentially disastrous consequences.

Other experiments show AIs can actively collect resources, accumulate power, and take proactive steps to prevent themselves from being ‘switched off.’ Credible studies suggest that at least some AI risks are not too overblown.

Compatible views?

The question is, can we trust ourselves with exceptionally powerful AI? ‘Ourselves’ being humans everywhere, at every level, from big tech research labs to the communities that build open-source AI.

Big tech may wish to consolidate market structures while fostering genuine concerns about AI’s future. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Meanwhile, the rise of open-source AI is inevitable, and regulation risks discontentment among a community that owns one of humanity’s most dangerous technologies.

It’s already too late to subjugate open-source AI through regulation, and attempting to do so could lead to a destructive era of AI prohibition.

Simultaneously, discussions surrounding AI’s dangers should be driven by the evidence – the only objective signal we have of the technology’s potential for harm.