Imagine playing the classic first-person shooter DOOM, but with a twist: the game isn’t running on code written by programmers; it’s being generated in real time by an AI system.

This effectively describes GameNGen, a breakthrough AI model recently unveiled by Google and Tel Aviv University researchers.

GameNGen can simulate DOOM at over 20 frames per second using a single Tensor Processing Unit (TPU).

Within that processing unit, we’re witnessing the birth of games that can essentially think and create themselves.

Instead of human programmers defining every aspect of a game’s behavior, an AI system learns to generate the entire game experience on the fly.

At its core, GameNGen uses a type of AI called a diffusion model, similar to those used in image generation tools like DALL-E or Stable Diffusion. However, the researchers have adapted this technology for real-time game simulation.

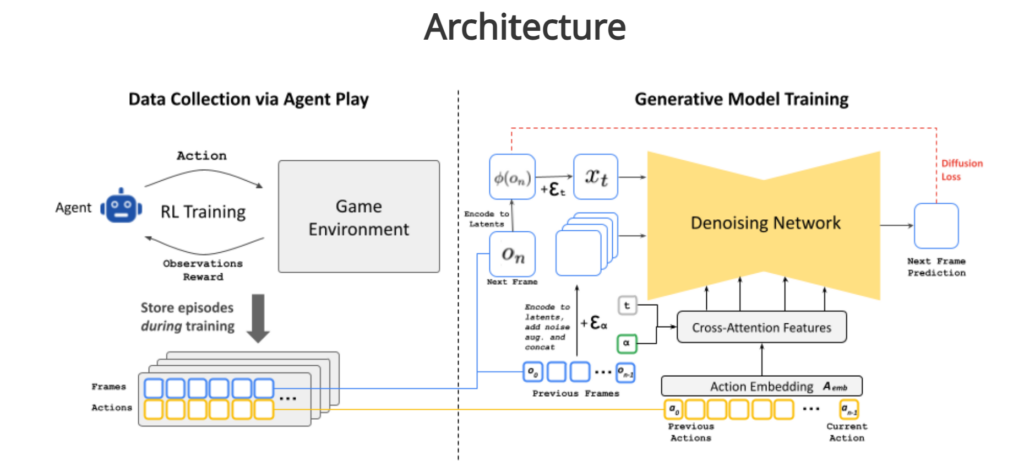

The system is trained in two phases. First, a reinforcement learning (RL) agent – another type of AI – is taught to play DOOM. As this AI agent plays, its gameplay sessions are recorded, creating a large dataset of game states, actions, and outcomes.

In the second phase, this dataset is used to train GameNGen itself. The model learns to predict the game’s next frame based on the previous frames and the player’s actions.

Think of it like teaching the AI to imagine how the game world would respond to each player’s move.

One of the biggest challenges is maintaining consistency over time. As the AI generates frame after frame, small errors can accumulate, potentially leading to bizarre or impossible game states.

To combat this, the researchers implemented a clever “noise augmentation” technique during training. They intentionally added varying levels of random noise to the training data, teaching the model how to correct and eliminate this noise.

This helps GameNGen maintain visual quality and logical consistency even over long play sessions.

While GameNGen is currently focused on simulating an existing game, its underlying architecture hints at even more exciting possibilities.

In theory, similar systems could generate entirely new game environments and mechanics on the fly, leading to games that adapt and evolve in response to player actions in ways that go far beyond current procedural generation techniques.

The path to AI-driven game engines

GameNGen isn’t emerging in isolation. It’s the latest in a series of advancements bringing us closer to a world where AI doesn’t just assist in game development – it becomes the development process itself. For example:

- World Models, introduced in 2018, demonstrated how an AI could learn to play video games by building an internal model of the game world.

- AlphaStar, from 2019. is an AI developed by DeepMind specifically for playing the real-time strategy game StarCraft II. AlphaStar utilizes reinforcement learning and complex neural networks to master the game, achieving excellent proficiency and competing against top human players.

- GameGAN, developed by Nvidia in 2020, showed how generative adversarial networks could recreate simple games like Pac-Man without access to the underlying engine.

- DeepMind’s Genie, unveiled earlier this year, takes things a step further by generating playable game environments from video clips.

- DeepMind’s SIMA, also introduced this year, is an advanced AI agent designed to understand and act on human instructions across various 3D environments. Using pre-trained vision and video prediction models, SIMA can navigate, interact, and perform tasks in diverse games without access to their source codes.

It all points towards a tantalizing future in which worlds can expand and respond to player actions with realism and depth.

Imagine RPGs where every playthrough is truly unique, or strategy games with AI opponents who adapt in ways no human designer could predict. Worlds that bend and flex to your character’s journey. Dialogue and interactions that look and sound like the real thing.

Amidst the excitement, we need to address the elephant in the room. The AI technologies driving futuristic gameplay also threaten to displace developers and designers.

GameNGen points to a potentially autonomous future for game design and development. And long before we reach that point, AI already threatens to shrink development teams across the software industry, including gaming.

Optimists argue this shift could free developers from manual drudgery, allowing them to focus on high-level design and storytelling within these new AI-driven frameworks.

For example, Marcus Holmström, CEO of game development studio The Gang, explained to MIT, “Instead of sitting and doing it by hand, now you can test different approaches,” highlighting the technology’s capacity for rapid prototyping and iteration.

Holmström continued, “For example, if you’re going to build a mountain, you can do different types of mountains, and on the fly, you can change it. Then we would tweak it and fix it manually so it fits. It’s going to save a lot of time.”

Borislav Slavov, a BAFTA-winning composer known for his work on Baldur’s Gate 3, similarly believes AI could push composers out of their comfort zones and allow them to “focus way more on the essence – getting inspired and composing deeply emotional and strong themes.”

But for every voice heralding the benefits of AI-driven game design, there’s another who isn’t so enamored by the prospect.

Jess Hyland, a veteran game artist and member of the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain’s game workers branch, told the BBC, “I’m very aware that I could wake up tomorrow and my job could be gone.”

For some, the fear of job displacement is in the crosshairs, as is the fundamental nature of creativity in game development.

“It’s not why I got into making games,” Hyland adds, expressing concern that artists could be reduced to mere editors of AI-generated content. “The stuff that AI generates, you become the person whose job is fixing it.”

Moreover, while AAA studios might see AI as a tool for pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, the picture could look very different for indie developers.

While AI game development could lower barriers to entry, allowing more people to bring their ideas to life, it also risks flooding the market with AI-generated content, making it harder for truly original works to cut through the noise.

Chris Knowles, a former senior engine developer at UK gaming firm Jagex, warns that AI can potentially exacerbate game cloning, particularly in the mobile market.

“Anything that makes the clone studios’ business model even cheaper and quicker makes the difficult task of running a financially sustainable indie studio even harder,” he cautioned.

There is a resistance brewing. The US SAG-AFTRA union, which launched the landmark Hollywood strike against production studios last year, recently initiated another strike over video game rights.

While it doesn’t strictly affect developers, the strike aims to prevent game studios from using AI to displace performers, like voice actors and motion performers, using AI without fair compensation.

The question is, how do you truly balance AI’s risks to the industry with the potential upsides for gamers, and gaming as an entire ecosystem? Can we really stop AI from revolutionizing an industry that prides itself on pushing technological boundaries?

After all, gaming is an industry that has truly relied on technology to progress.

Earlier in the year, we spoke to Chris Benjaminsen, co-founder at AI game startup FRVR, who explained to us:

“I don’t think the world has had truly user-generated games yet. We’ve had user-generated games platforms where people were generating UGC, but it’s always been limited with some of the capabilities that whatever platform supported, right? If you have a platform with a bunch of templates for puzzle games, you get a bunch of puzzle games, but you can’t create unique games on any platform that just supports templates. I think that AI can change everything.”

Benjaminsen argues that this allows people to drive game creation from the ground up. It acts as an antidote to large-scale developers who select projects based on their financial returns.

“Rather than having very few people decide what games people should be allowed to play, we want to allow anyone to create whatever they want and then let the users figure out what is fun. I don’t believe most of the games industry knows what people want. They just care about what they can make the most money on.”

It’s a pertinent point. Amidst all the industry disruption, we can’t lose sight of the most important stakeholder: the players.

Advances in personalized gameplay, combined with granting people the power of choice over their gaming experiences, could usher in a new era of play-driven gaming experiences.

Yes, developer jobs will likely get squeezed like many others across the creative industries. It’s never ideal for people to lose their jobs, but it salts the wound when those changes also compromise the quality of the products they once loved creating.

There is hope, however, that AI’s role in gaming will be more likely to lead to wholesome outcomes than in visual arts or film & TV. Game developers could also find it easier to adapt to and work alongside AI tools rather than being replaced by them.

This contrasts with fields like music, where AI can generate products directly competing with human artists. The technical complexity of game development may also create a more complementary relationship between AI and human creativity than a purely competitive one.

In the end, AI’s impacts on game development will be debated for years to come. Like any powerful tool, its impact will depend on a variety of stakeholders, from the players to the studios.

Will AI continue to push the boundaries of interactive entertainment? Or will we allow it to homogenize game development, sacrificing the unique visions of human creators on the altar of efficiency?

The answer, like the future of gaming itself, and indeed that of many other creative industries, is yet to be written. But one thing is certain: the controller is in our hands for now.

How we play this next level will determine the course of the game industry for generations to come.