Back in 1956, Philip K. Dick authored a novella titled “The Minority Report” that spun a web of a future where “precogs” could foresee crimes before they transpired in reality.

A few decades later, Tom Cruise brought this eerie vision to the big screen, chasing would-be criminals based on these predictions.

Both versions forced us to contemplate the ethical implications of being arrested for something you might do in the future.

Today, as predictive policing methods worm their way into modern law enforcement, one must wonder: are we on the cusp of realizing Dick’s prescient narrative?

What is predictive policing, and how does it work?

Predictive policing melds law enforcement and advanced analytics, harnessing machine learning to anticipate criminal activities before they unfold.

The premise is straightforward enough on paper: if we can decode the patterns hidden within historical crime data, we can craft algorithms to forecast future occurrences.

The process starts with amassing historical crime records, surveillance feeds, social media chatter, and even nuances like weather fluctuations. This vast repository of information is then fed into sophisticated machine learning models designed to discern underlying patterns.

For example, the model might discern that a specific neighborhood witnesses a spike in burglaries on rainy weekend nights.

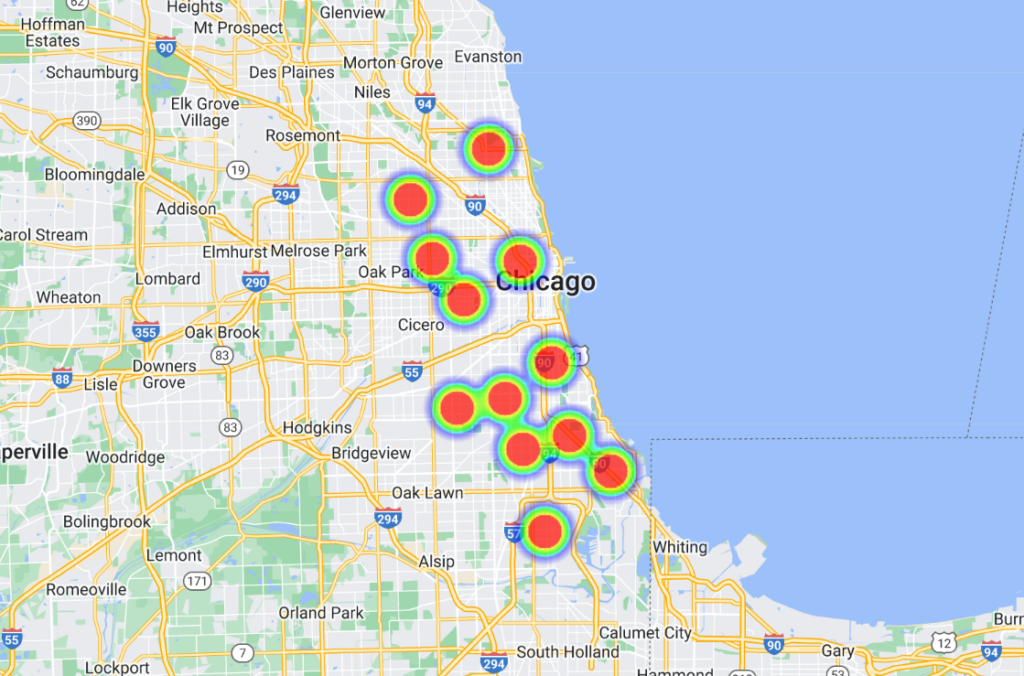

Once these correlations are teased out, advanced software platforms transform them into visual representations, often resembling ‘heat maps’ highlighting probable crime hotspots. This, in turn, empowers the police to allocate their resources proactively, optimizing their patrols and interventions.

Some models have gone a step further to list people by name and address, equipping officers with highly specific and localized predictions.

The history of predictive policing

Predictive police technology is still embryonic, and while there have been some influential players in the industry, like Palantir, the industry is small.

In June 2022, the University of Chicago developed an AI model capable of forecasting crime locations and rates within the city with an alleged 90% precision.

Drawing upon open crime data from 2014 to 2016, the team divided Chicago into approximately 1000ft (300m) squares. The model could predict, a week in advance, the square with the highest likelihood of a crime occurrence.

The study had honest intentions, unearthing spatial and socioeconomic biases in police efforts and resource allocation. It found that affluent neighborhoods received more resources than lower-income areas.

In the study’s words, “Here we show that, while predictive models may enhance state power through criminal surveillance, they also enable surveillance of the state by tracing systemic biases in crime enforcement.”

Additionally, the model was trained using data from seven other US cities, showing similar outcomes. All datasets and algorithms have been made available on GitHub.

Chicago is an important case study in data-driven and AI-aided policing. Another example is the city’s gun crime heatmap, which identifies crime “hotspots” that can be fed into policing efforts.

A notable incident back in 2013 – in the infancy of predictive policing – involved Robert McDaniels, a resident of Chicago’s Austin district, which accounts for 90% of the city’s gun crimes.

Despite his non-violent record, McDaniel’s inclusion in a list of potentially violent criminals saw him twice become a target of gun violence by virtue of the police turning up on his door and making him a target.

An investigation by The Verge states that a journalist from the Chicago Tribune contacted McDaniel regarding the “heat list” — an unofficial name that police assigned to the algorithms that label potential shooters and targets.

Ishanu Chattopadhyay, the lead researcher in the 2022 Chicago crime prediction project, emphasized that their model predicts locations, not individuals. “It’s not Minority Report,” he said – but the McDaniels event certainly draws some parallels.

Addressing concerns of bias, Chattopadhyay noted that they intentionally omitted citizen-reported minor drug and traffic infractions, focusing on more frequently reported violent and property crimes.

However, studies show that black individuals are more frequently reported for crimes than their white counterparts. Consequently, black neighborhoods are unfairly labeled as “high risk.”

Moreover, intensified policing in an area means more reported crime, creating a feedback loop that distorts crime perception.

Then, relying on past data can perpetuate stereotypes and overlook the potential for change and rehabilitation.

How has predictive policing fared?

Predictive policing, unsurprisingly, is highly contentious, but does it even work or fulfill its basic purpose?

An October 2023 investigation by The Markup and Wired revealed glaring failures, adding to a growing volume of evidence highlighting the perils and shortcomings of transferring law enforcement decision-making to machines.

The program in focus is Geolitica, a predictive policing software used by the police in Plainfield, New Jersey. It’s worth noting that Plainfield’s police department was the only one out of 38 departments willing to share data with the media outlets.

Previously known as PredPol, this machine learning software was acquired by various police departments.

The Markup and Wired analyzed 23,631 of Geolitica’s predictions from February to December 2018. Out of these, less than 100 predictions matched real crime instances, resulting in a success rate of less than half a percent.

These prediction models have always been contentious, raising numerous ethical questions regarding their potential to reinforce discriminatory and racist biases prevalent in AI and law enforcement.

This recent investigation underscores ethical dilemmas and questions the software’s efficacy in predicting crimes.

Though the software showed slight variances in prediction accuracy across crime types (e.g., it correctly predicted 0.6 percent of robberies or aggravated assaults compared to 0.1 percent of burglaries), the overarching narrative remains one of gross underperformance.

Plainfield PD captain David Guarino’s candid response sheds light on the ground reality. “Why did we get PredPol? We wanted to enhance our crime reduction efficiency,” he commented.

“I’m not sure it achieved that. We rarely, if ever, used it.” He also mentioned that the police department discontinued using it.

Captain Guarino suggested that the funds allocated to Geolitica – which amounted to a $20,500 annual subscription fee plus an additional $15,500 for a second year – might have been more effectively invested in community-centric programs.

Geolitica is set to shut down operations by year’s end.

Evidence documenting bias in predictive policing

The promise of predictive policing remains tantalizing, particularly as police forces are increasingly stretched and the quality of human police decision-making is brought into disrepute.

Police forces in the US, UK, and several European countries, including France, face scrutiny over prejudice towards minority groups.

Members of both the UK’s House of Lords and Commons are urging for a temporary halt on the deployment of live facial recognition technology by the police.

This emerged after policing minister Chris Philip discussed granting police forces access to 45 million images from the passport database for police facial recognition. Thus far, 65 parliamentarians and 31 rights and race equality organizations oppose using facial recognition technologies in policing.

The advocacy group Big Brother Watch stated that 89% of UK police facial recognition alerts fail in their purpose, with disproportionately worse results for ethnic minority groups and women. A 2018 facial recognition trial by the London Metropolitan Police had a dismal success rate of only about 2%.

As Michael Birtwistle, from Ada Lovelace Institute, described, “The accuracy and scientific basis of facial recognition technologies is highly contested, and their legality is uncertain.”

In the US, a collaborative project involving Columbia University, AI Now Institute, and others recently analyzed US courtroom litigations involving algorithms.

The study found that AI systems were often implemented hastily, without appropriate oversight, mainly to cut costs. Unfortunately, these systems often resulted in constitutional issues due to inherent biases.

At least four black men have been wrongly arrested and/or imprisoned pending incorrect facial matches in the US, including Nijeer Parks, falsely accused of shoplifting and road offenses despite being 30 miles away from the alleged incidents. He subsequently spent ten days in jail and had to pay thousands in legal fees.

The study authors concluded, “These AI systems were implemented without meaningful training, support, or oversight, and without any specific protections for recipients. This was due in part to the fact that they were adopted to produce cost savings and standardization under a monolithic technology-procurement model, which rarely takes constitutional liability concerns into account.”

Predictive policing may encourage unnatural decision-making

Even when predictive policing is accurate, humans need to act on the predictions, which is where things get messy.

When an algorithm tells the police they need to be somewhere because a crime is being/is likely to be committed, it’s far from infeasible to think this distorts decision-making.

There are a few basic psychological theories it would be wise to confront when considering AI’s role in policing.

Firstly, when an algorithm informs the police of a likely crime scene, it potentially primes them to view the situation through a lens of expectancy. This might’ve played a hand in the McDaniels incident – police arrived on the scene expecting an incident to take place, triggering events to escalate amid a volatile environment.

This is rooted in confirmation bias, suggesting that once we have a piece of information, we tend to seek out and interpret subsequent information in a manner that aligns with that initial belief.

When someone is told by an algorithm that a crime is likely to occur, they may unconsciously give more weight to cues that confirm this prediction and overlook those that contradict it.

Moreover, algorithms, especially those used in official capacities, can be viewed as authoritative due to their computational nature, and officers might place undue trust in them.

And then there’s the risk of moral disengagement. Officers may shift the responsibility of their actions onto the algorithm, thinking that it’s the software that made the call, not them – which is also highly relevant in the field of warfare.

Debates here parallel with those surrounding AI’s use on the battlefield, which poses some similar dilemmas.

The imposed authority of AI can result in an “accountability gap” where no one takes responsibility for mistakes made by the AI, as highlighted by Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz in a recent JSTOR article.

All in all, from the current evidence we have, predictive policing often perpetuates rather than diminishes biases.

When predictions combine with human decision-making, the impacts are potentially catastrophic.