The US film and TV industry was hit with a dual strike this year, the first since 1960.

The WGA strike commenced in May, preceding the high-profile Hollywood Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) actors strike. SAG-AFTRA joined the WGA in a double strike in July.

After 146 days on strike, the WGA announced they’d arrived at a deal with producers from the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), signaling the first official industry protections against AI.

At the outset of the WGA strike, Michelle Amor, a recognized figure in Hollywood scriptwriting, said, “I don’t want to be replaced with something artificial,” adding, “We writers are the heart and soul of this entire industry. No one works until we do – everyone knows it.”

Writers from the WGA demanded clear boundaries on the deployment of AI tools in the entertainment industry in addition to other financial guarantees. Members of the SAG-AFTRA union currently remain on strike.

The WGA’s 2023 basic agreement: an overview

The WGA finalized an agreement spanning September 25, 2023, to May 1, 2026, ensuring member protections and benefits for the next three years. It’s set to be ratified by a vote in early October.

Who knows what happens after those three years are up, as AI is certain to have advanced massively, and the goalposts are sure to have moved.

As for the deal, first, members of the WGA are set for immediate financial benefits with a 5% pay raise, adjusting to 3.5% by 2025. Additionally, there will be a 0.5% increase in Health Fund contributions starting from the second year and favorable changes to compensation structures.

Further, screenwriters for high-budget streaming features will see an 18% rate hike while residuals (royalties) are adjusted in line with international viewership metrics. Furthermore, writers for ad-supported streaming platforms will have terms comparable to those in subscription-based services, with added regulations for platforms like Netflix and Hulu.

In terms of AI, the WGA has gained assurance that AI tools cannot be used to totally write or modify scripts. Additionally, AI will have no say in determining credits, ensuring writers receive full recognition for their work.

While writers can employ AI tools to aid their process, there is a strict provision against forcing them to use such technologies.

It’s important to recognize also that AI is intertwined with other financial aspects like residuals, as film and TV are gradually moving away from big hit blockbuster grandiosity to more series-based and short-form ‘content’ – a word that has become increasingly political.

Emma Thompson, the Oscar-winning actor and screenwriter, candidly expressed her discomfort with the term ‘content’ at a recent conference. “To hear people talk about ‘content’ makes me feel like the stuffing inside a sofa cushion,” she remarked, suggesting that the term is an affront to creators who pour their souls into their work.

“It’s just a rude word for creative people,” Thompson continued, likening it to calling their artistic creations mere “debris.”

It’s a pretty good point. The word ‘content,’ like the term ‘widget’ from the 1986 film “Back to School,” has become an all-encompassing term that might be seen to undervalue the individuality and nuance of creative work.

Where once we differentiated between movies, series, podcasts, and more, now it’s all just ‘content’ – a term as nondescript as ‘widget.’

Semantics? Possibly, but AI and the ‘content era’ do work well together.

Why AI poses a problem for writers and actors

It’s the shift away from human-driven authentic work to digitally-empowered ‘efficiency’ that many are worried about.

While AI poses all sorts of problems for creatives of every stripe, writing is perhaps among the most obvious grounds for the technology to seize, hence why actors took action so early on. That was a prescient move, as securing protection until 2026 means shielding against a new round of AI model releases that will place jobs under greater pressure.

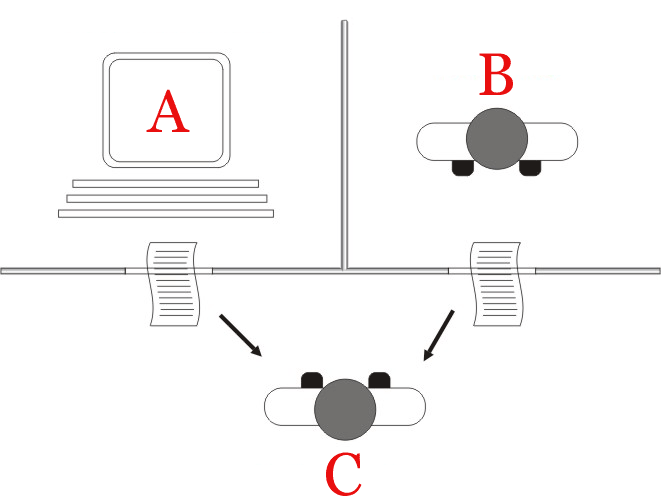

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are creatively limited and produce intrinsically derivative outputs, but the issue isn’t so much about replacing writers with 100% AI-generated content.

Rather, writers argued that producers could pass a small amount of genuine content into the model to proliferate it into numerous ideas, capturing some of the essence of authentic work and injecting it with the scalability of AI.

For members of the actor’s SAG-AFTRA union, the pressure on jobs is much the same as for the WGA – AI can replace them – but the medium through which that could happen is potentially more jarring and dystopian.

Actors fear AI will copy them and their ‘likeness’ and use it to represent them in shows digitally.

This is already happening, as actors are already ‘scanned’ for the sake of CGI, and that data can potentially be used to reconstruct them without them being present.

As Samuel L. Jackson described, “Ever since I’ve been in the Marvel Universe, every time you change costumes in a Marvel movie, they scan you.”

Startups are now using AI technology to ‘resurrect’ actors like James Dean from the dead.

Instead of hiring actors or bothering with new, upcoming talent, producers could simply dig into a box of digital clones and select their preferred AI copy. While actors would have to give their permission, contract terms could gaslight them into doing so.

While the practical impacts on people’s livelihoods are center stage, the role of AI goes beyond mere tool usage. It delves into the very essence of storytelling.

As Melissa Rundle described, “AI doesn’t have childhood trauma. As writers, we are creating stories that touch people and oftentimes digging deep into our soul – this is storytelling at its most sacred and should never be robbed by a machine.”

This argument, though compelling, doesn’t necessarily stand up to the test if we query how LLMs work. While AI models like GPT-3.5/4 are informational systems with no emotions or inherent humanity, they’re excellent at imitating us. This is the founding premise of Alan Turing’s Turing Test, initially named the “Imitation Game.”

Perhaps it is scarier to consider that AI doesn’t have to be nearly as intelligent or emotional as us to replace us, so long as it’s good enough at imitating.

AI can channel childhood trauma as it ‘understands’ it semantically, underlining the technology’s ability to bypass what many would consider humanity’s creative soul by elegantly copying it.

Public responses to the strikes

Hollywood as an environment – a microcosm – has come under fire in recent years – with people from various political leanings decrying its elite as woefully out of touch.

There is perhaps no more scything description of this than Ricky Gervais’ ultra-controversial monologue at the 2020 Golden Globes.

In his words: “Apple roared into the TV game with The Morning Show, a superb drama about the importance of dignity and doing the right thing, made by a company that runs sweatshops in China. Well, you say you’re woke but the companies you work for in China — unbelievable. Apple, Amazon, Disney. If ISIS started a streaming service you’d call your agent, wouldn’t you?”

He pressed on despite winces from Tom Hanks and others, stating, “So if you do win an award tonight, don’t use it as a platform to make a political speech. You’re in no position to lecture the public about anything. You know nothing about the real world. Most of you spent less time in school than Greta Thunberg.”

This sentiment repelled some passive observers from the cause of Hollywood’s strikes.

Yes, it is tough to sympathize with Hollywood A-listers taking a break from their assignments to join the picket lines, but that doesn’t give fair credit to the plight of SAG-AFTRA’s 160,000+ other members and thousands of writers and creative workers aside.

Overall, most discussions see that Hollywood, at the Western cultural cutting edge, is perhaps the right testing ground for combating AI job replacements.

As investor and AI researcher Paul Kedrosky told Vanity Fair, “The writers strike is too easily dismissed as coastal elites protecting their cushy gigs. Instead it should be seen as the first skirmish in a new war, one where more than half of all jobs are at risk as we lose control of language itself—and thus of being human—to large language models.”

SAG-AFTRA’s ongoing protest

SAG-AFTRA announced they were pleased with the WGA’s resolution but remain on strike for the foreseeable future.

The dialogue between SAG-AFTRA and producers has been bitter, with President Fran Drescher fervently explaining that “the AMPTP’s maniacal corporate culture for greed must stop.”

With the WGA settled until 2026, many are anxious to get Hollywood rolling again, and so both SAG-AFTRA and the AMPTP announced their intentions to resume negotiations on Monday, October 2.

A joint statement stated, “SAG-AFTRA and the AMPTP will resume negotiations for a new TV/Theatrical contract on Monday, Oct. 2. Several executives from AMPTP member companies will be in attendance.”

The studios’ stance

Studios, historically at the forefront of embracing new technologies, are in a tight spot.

Scott Rowe, representing The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), is sympathetic, stating, “We’re creative companies and we value the work of creatives.”

Rowe also understands the writers’ desire to use AI when advantageous without compromising their credit, a complex issue since AI-generated content isn’t subject to copyright.

As Hollywood finds itself at this crossroads, the ongoing strike serves as a pivotal moment for creative industries worldwide.

With studios incessantly looking for ways to cut costs, AI emerges as an attractive proposition for streamlining operations.

While the capabilities of current AI large language models like ChatGPT and Bard might be circumscribed in producing deeply authentic, creative content, the horizon of technological advancements is ever-expanding.

The pressing question remains: when the lines between AI and human creativity blur even further, who will studios prioritize – the human touch or the efficiency of AI? How much time do people have to adapt if it’s the latter?

The path ahead

In the dim, softly lit world of Rick’s Café Américain, where Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine and Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa Lund rekindled a love story against the backdrop of war-torn Casablanca, there was an unmistakable magic. A cinematic alchemy that transformed a script, actors, and sets into an experience that transcended its components – a cinema archetype that many wished to follow.

“Casablanca,” like so many other tremendous cinema productions, aren’t just films – they’re a sweeping testament to human emotion and ingenuity. Similar can be applied to other art forms, particularly music – and it just makes you wonder whether all the classics are behind us and what lies in front is just ‘content.’

Fast forward to our current era – a time when a short, snappy viral video can garner millions of views in a matter of hours. These videos cater to a desire for immediate gratification – a quick, fleeting high that dissipates almost as soon as it hits.

This isn’t to say that viral clips lack value. They capture moments, often genuine, that resonate with vast audiences. They represent the democratization of storytelling, where anyone with a camera phone can share a piece of their world.

However, it’s finely balanced. As platforms scramble to fill their libraries, there’s a danger in treating all content as interchangeable.

The commercial impetus for this is clear – there’s an ever-growing push for scalability in a world dominated by algorithms and AI. Algorithms barely differentiate between classics and viral hits – they prioritize what’s popular, current, and likely to keep viewers engaged for that next click or episode.

We don’t yet know where AI leaves human creativity, but Hollywood won’t be its last battleground.