An innovative pilot project in Devon, South-west England, is leveraging AI to predict and mitigate pollution issues before they occur, focusing on improving the water quality at Combe Martin, a popular seaside resort.

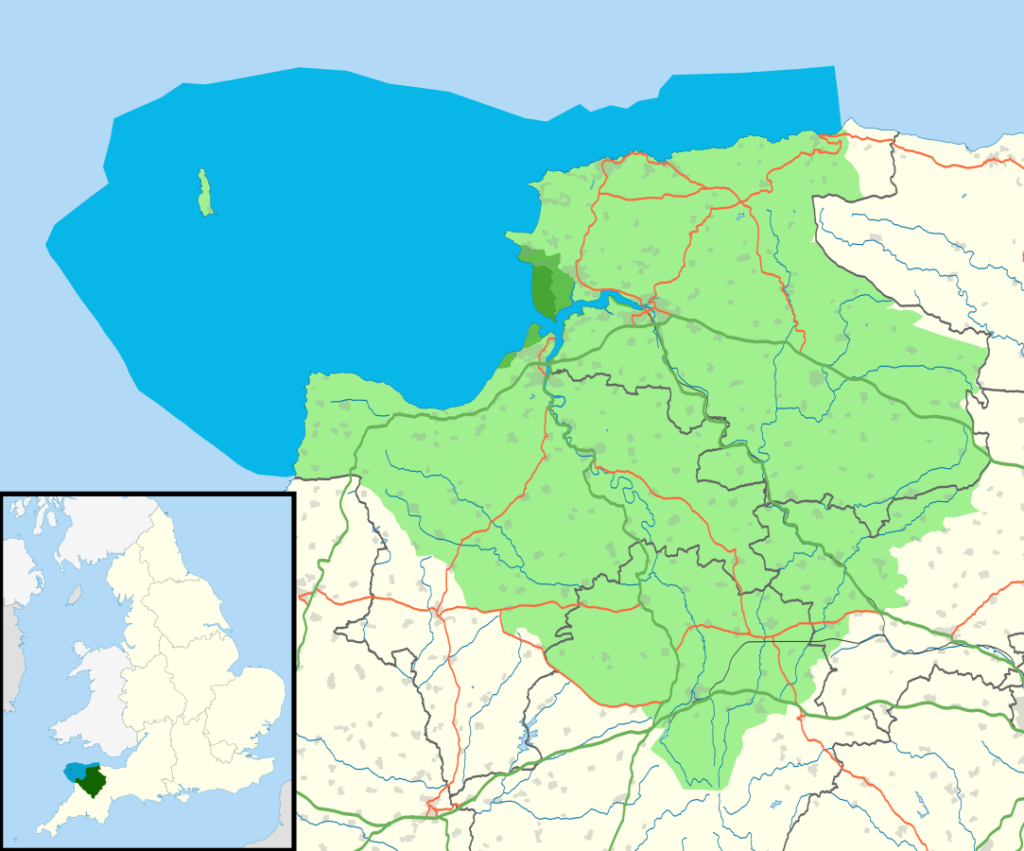

The North Devon UNESCO Biosphere Reserve covers 55 square miles and is centered on Braunton Burrows, England’s largest sand dune system.

The AI technology uses sensors stationed in rivers and fields to capture real-time data about the local rivers’ status, rainfall patterns, and soil conditions.

This information is combined with satellite imagery, allowing the AI to forecast when the local river system might be at risk from hazards like agricultural runoff. Agricultural run-off occurs when fertilizer washes into rivers and waterways.

Tech firm CGI is leading the project in collaboration with mapping experts Ordnance Survey.

The project forms part of the Sustainability Exploration Environmental Data Science (SEEDS) program in collaboration with the United Nations (UN).

Mattie Yeta, Chief Sustainability Officer for CGI, said, “Following a successful first phase of the project, which led to the creation of an AI and satellite tool that can predict pollution events with up to 91.5% accuracy, we are excited to launch this second phase, which provides an innovative and proactive approach to environmental management and nature protection.”

“We’ll provide the AI with the history, geographical information, and sensor data, which will enable it to learn and develop predictive mechanisms that can indicate where and when pollution incidents might occur,” explained Yeta.

What does it solve?

Combe Martin, a seaside resort town in south England, has a history of fluctuating water quality.

However, recent evidence suggests that water quality is declining to the detriment of local communities and the natural environment. “The water quality has been consistently low,” commented Andy Bell from the North Devon Biosphere Reserve.

The River Umber, which flows through the reserve, is often polluted by a sewage treatment plant and agricultural runoff from farm fertilizer. When the water quality is particularly poor, tourists are unable to swim in the sea, which damages local businesses.

The AI looks at several metrics to determine when a pollution event could occur. “We would see spikes in indicators like ammonia and pH if sewage was being discharged upstream,” said Glyn Cotton, the CEO of environment-focused tech company Watr who collaborated on the project.

The project leverages approximately 50 connected sensors spread across the reserve. Sensor data combines mapping and satellite data to plot when and where pollutants are dedicated.

The AI model is designed to predict pollution events in time for local stakeholders to prevent them. For instance, it could suggest to a farmer to stop fertilizing their field if the forecast predicts heavy rain that could wash the fertilizer into the waterways.

“The solution will benefit farmers, governments, water companies, and other stakeholders by protecting our water from pollution and contamination, which is vital for both our way of life and the life of our waterways and coast lines,” continued Yeta, adding, “We’re starting small here in North Devon, but the ultimate aim is to expand and implement this strategy in different parts of the UK.”

AI’s innovative small-scale applications emphasize the technology’s potential for benefit.

For example, researchers in Norway and the UK use an AI model to detect invasive Pacific salmon in European waterways, helping them protect native species.

AI is a phenomenal technology for solving novel problems, and researchers worldwide are taking advantage for the benefit of both people and the environment.